Evidence Based Practice

PTA 101 - Introduction to Clinical Practice 1

Lane Community College PTA Program attributes the following to Neil Henry of the Scottish Social Services Council. Material is replicated or derived through Creative Commons License 2.5 (CC - BY-SA2.5).

The following information is used for instructional purposes for students enrolled in the Physical Therapist Assistant Program at Lane Community College. It is not intended for commercial use or distribution or commercial purposes. It is not intended to serve as medical advice or treatment.

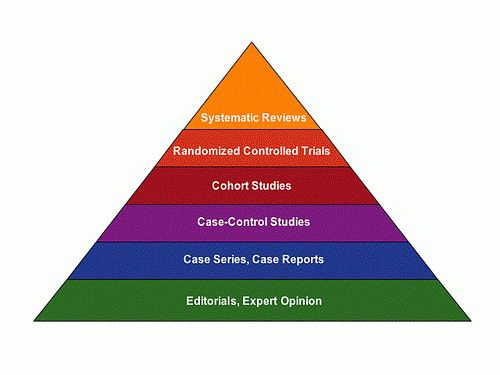

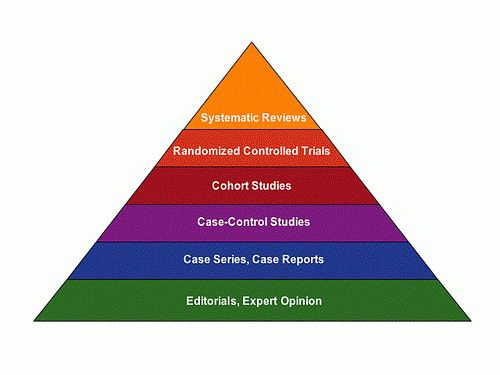

(image courtesy of uncg.libguides.com)

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is a term that is often confused in its understanding and application. For certain, best practices in physical therapy include techniques and interventions supported in the scientific literature. However, EBP, includes the integration of patient/client experience and goals and the experience of the health care provider. This triad: the research, the practitioner, and the patient, are the core elements of evidence-based practice.

In PTA 100, we discussed EBP in regards to the PT Guide to Practice. In this lesson, we will introduce the use of EBP in clinical practice and explore opportunities and methodology in formulating answerable clinical questions.

By the end of this lesson, the student should be able to:

This section looks at types of clinical decision-making and in particular the difference between practical knowledge and the kind of knowledge found in research. In patient care, Evidence-Based Practice is a triad of influences: Patient - Provider - Research.

When we talk about 'Evidence Based Practice' we mean providing physical therapy to our patients and clients using methods that are supported practice patterns, clinical reasoning, and research. In this section, we ask the question: when are everyday clinical practice patterns enough and when do we need to go research for evidence of clinical effectiveness for PT interventions? From single case studies to statistical analysis of multiple studies, PTs and PTAs are charged to constantly refine, implement, and assess treatment techniques and outcomes so we may develop our "best practices" as a profession.

The following exercise is adapted from work done by the National Center for the Study of Adult Learning and Literacy [NCSALL, 2007].

Please spend a moment or two drawing both sides of a penny. It is important that you do this entirely from your own memory and without looking at a real example of a penny. Once you have finished please compare your drawing with a real penny

![]()

Now complete the activity below to relate the photo album activity to clinical reasoning

![]()

There are a number of implications for your role as PTA. Firstly, given your role in assessing treatment response and outcomes, it is important to clarify and test out your subjective impressions of the patient's performance/outcome with some hard evidence. On what exactly do you base your view of the treatment outcome? It can very much help to have the views of others as these can help you to tell the difference between your subjective impressions and a more objective view. The more objective view is one that others also see.

If you are the only one with a particular impression it may be worth questioning yourself as to whether this view is well founded or not.

Secondly, you need to practice developing the habit of always basing your own assessments on clear evidence and justifying your choice of method by pointing to retrievable evidence. To find strong evidence you need to search the literature (and we will show you the way!)

Consider the following:

Please take a few moments to record your answers to these questions before revealing the next part of the discussion

![]()

This section considers some of the attitudes to research held by practitioners. These range from completely dismissing the relevance of research to embracing the opportunity to look at all aspects of practice anew. A key consideration here is the link between practice and theory. By listening to and considering practitioners' views you will be able to identify some of the ways research can enhance practice and understand some of the barriers.

Please consider the following three statements and highlight the one that most closely corresponds to your own view:

These three statements broadly conform to three positions on research taken up by groups of teachers studied by Zeuli & Tiezzi (Reference: Creating contexts to change teachers' beliefs about the influence of research 1993. 6/1/09).

As PTAs you may see similar positions taken up by colleagues.

The activities below are based on three practitioner scenarios.

Once you have completed your reflections you can click on the 'Did You Know' below to compare your thoughts.

![]()

![]()

![]()

In week 10, we will discuss a famous editorial by Sackett et al., on evidence based practice that summarizes what EBP is, and more importantly what it is NOT and key points the WEek 10 articles will be assessed on the Unit 3 exam.

Evidence Based Practice relies on background knowledge of disease and disorder to formulate a clinical question. While respecting scope of practice, a PTA should be able to self-identify a need for more information, research the question, and appropriately apply the outcome of the researched information in clinical practice. Steps in Implementing EBP can be summarized as follows:

Consider a scenario you have recently practiced in lab to reinforce how clinical reasoning, and reflecting on clinical reasoning and evidence, reinforces your understanding and effectiveness in applying electrical stimulation to a clinical case:

Henry is a 55 yo male 7 days s/p L RTC repair in a sling with pain rated 9/10 immediately following PROM exercises last visit. He has not been taking his pain medication regularly due to stomach irritation. Decreasing pain and increasing PROM are treatment goals and therex, pain management, patient education, modalities, and functional training is in the plan of care. The PT has asked you to select a modality for symptom management and to help progress the patient. The pt. is not allowed muscle contraction for 3 more weeks.

1. What is our clinical purpose in this situation? Is there a need for additional information?

2. Evidence: PTA 101lecture, Dutton text, web searches, lab experiences

3. Evaluate: What modality will you select based on your research?

4. What additional "evidence" (clinical reasoning, patient information and feedback) will you use to finalize your treatment approach?

5. What tests, measures, or other data will you collect to help determine the treatment outcome?

6. Was the treatment outcome expected or unexpected? Why? What, if anything, will be done differently?

7. Repeat all these processes next visit.....

In short, evidence-based practice and active clinical reasoning are integrating. Thinking about your thinking and questioning assumptions and reasons for outcomes will prompt more questions....

(just for fun)

http://www.ted.com/talks/stuart_firestein_the_pursuit_of_ignorance.html )

Librarians are experts in how to access and search for information. LCC has excellent library faculty and staff to help guide your research efficiently and effectively.

Evidence-based practice hinges on our ability to formulate (and then answer) a question. This research guide will help structure your research methods

Are you new to LCC or new to using LCC as a source for books and articles? Use the Ask a Librarian library feature to get personalized help:

Evidence-based practice starts with a question:

What is the best intervention for this patient/client?

In clinical research, some questions are intended to lead toward a deeper understanding of the background of a disease or condition. Other studies ask foreground questions in order to analyze patterns and for predicting outcomes based on a given set of conditions.

What are the effects of electrode size on patient comfort during large muscle NMES treatments?

Why are supraspinatus muscles the most commonly torn rotator cuff muscle?

When is it safe for adolescents to initiate a weight training program?

How does pulsed ultrasound enhance the inflammatory response in superficial soft tissue?

Foreground questions ask for specific knowledge to inform clinical decisions or actions. There are four general categories of foreground questions:

A foreground question should contain for main elements in order to increase the specificity and applicability of the answer to the question. The acronym PICO is used to recall the four essentials of a foreground question:

Patient/Problem/Population - identifies who you are limiting your question to

Intervention - identifies the specific circumstances or conditions of treatment

Comparison - related to another patient/problem/population and/or intervention (e.g., control groups)

Outcomes - result of the intervention (e.g.., least, most, best, longest duration, fall frequency, patient satisfaction, etc.)

Now, go back to the LCC Research Guide to think about forming a good question

Answerable foreground questions rely on specific constraints or conditions to address a specific problem through standardized quantitative and/or qualitative measures. Once you have crafted a good question, you will be able to proceed with a directed search of the evidence to-date which addresses your clinical question. Useful resources (databases) to answer foreground questions are:

Many databases can be searched for specific levels of evidence on a research topic. Levels of evidence are discussed in more detail in this lecture.

The LCC Library offers access to many databases. In many cases, you have free access to full text articles if you access related databases through the LCC Library website. Your APTA membership is another great resource that you can take with you after you leave Lane and move into clinical practice.

This 6-minute video provides an example of how to use PICO strategies in APTA's Article Search and in PubMed to search keywords.

Other sources of evidence include links and publications through national authorities, like the Center for Disease Control and the National Institutes of Health (CDC, NIH)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

review and analysis of randomized controlled trials

From reading a professional journal to performing an advanced search in a database, a PTA can evaluate the level of evidence available for a research (foreground) question.

Level I

|

Systematic review of meta analysis of all relevant randomized controlled trials or evidence based on clinical practice guidelines based on systematic review of RCTs

|

Level II

|

Evidence obtained from at least one properly designed randomized controlled trial

|

Level III

|

Evidence obtained from well designed controlled trials without randomization

|

Level IV

|

Evidence obtained from well designed case controlled and cohort studies

|

Level V

|

Evidence from systematic reviews of descriptive and qualitative studies (meta-synthesis)

|

Level VI

|

Evidence from a single descriptive or qualitative study

|

Level VII

|

Evidence from opinion or authorities and/or reports of expert committees

|

The APTA adopted the Vision 2020 statement to frame the role of the PT by the year 2020, which includes attention to evidence-based practice.

Evidence-based practice is access to, and application and integration of evidence to guide clinical decision making to provide best practice for the patient/client. Evidence-based practice includes the integration of best available research, clinical expertise, and patient/client values and circumstances related to patient/client management, practice management, and health care policy decision making. Aims of evidence-based practice include enhancing patient/client management and reducing unwarranted variation in the provision of physical therapy services.

Source: http://www.apta.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Research&TEMPLATE=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&CONTENTID=39951. Cited 11.15.09

In our EBP discussion forum, consider the lecture material and Sackett editorial when posting and responding to the discussion question.