Introduction to Motor Learning

PTA 101 Introduction to Clinical Practice 1

Instructional Use Statement

The following information is used for instructional purposes for students enrolled in the Physical Therapist Assistant Program at Lane Community College. It is not intended for commercial use or distribution or commercial purposes. It is not intended to serve as medical advice or treatment.

Contact howardc@lanecc.edu for permissions

Introduction to Motor Learning

An exercise is a movement or muscle activation. Literally, every time a skeletal muscle is volitionally activated, it is exercising.

The distinction between exercise instruction and motor learning for functional recovery is that individuals demonstrate they have learned movement when they can select a movement/activity and apply it in task-specific situations.

Motor learning requires practice, feedback, and knowledge of results.

Motor learning leads to skill, as your patient/client progresses from simple to complex tasks within controlled and open environments. Motor learning is influenced by the patient/client age, motivation, learning style, and cognition.

Learning Objectives

Students at the end of this lesson will be able to:

- Define stages of motor learning that guide intervention planning and assessment

- Describe a skill according to motor task taxonomy

- Distinguish between types and characteristics of effective practice and feedback

- Apply a motor task analysis framework to a simulated patient situation

- Consider communication strategies that may enhance motivation, participation, and motor performance, and motor skill

Motor Learning Terms

Skill:

a learned sequence of movements that combine to produce a smooth, efficient action in order to master a particular task1

- Includes a high degree of precision and accuracy with movement.

- Performance is the execution of a motor skill at a point in time; demonstration of skill acquisition

Types of motor skills include:

- gross motor: total body and/or limb movements; typically requires a significant amount of muscular involvement

- fine motor: little body movement; primarily involving use of hands in manipulating objects

Learning:

Performance and RETENTION of the motor skill. Motor learning is the result of experience and practice.

Performance = Can your patient do the movement task? Is the movement task of high quality and precision? (This is observable)

Learning = Could your patient do the same task tomorrow? Under different conditions? With distractions? (An internal process: this can not be observed, but is inferred through observation of performance)

Motor task classifications

Discrete task: has a beginning and an end. Examples include locking wheelchair breaks, activating a push button

Serial task: a series of predictable steps to complete a task. Examples opening a locked door: key in lock, turn key, twist or press door handle. The series is important, because each subsequent step relies on correct completion of the preceeding step. For example a key in the lock will not open the door when the handle is pressed unless the key is turned first

Serial task: a series of predictable steps to complete a task. Examples opening a locked door: key in lock, turn key, twist or press door handle. The series is important, because each subsequent step relies on correct completion of the preceeding step. For example a key in the lock will not open the door when the handle is pressed unless the key is turned first

Continuous task: repetitive with no distinct beginning or end, requiring repetition of movement patterns. Many forms of cardiovascular exercise are considered continuous tasks

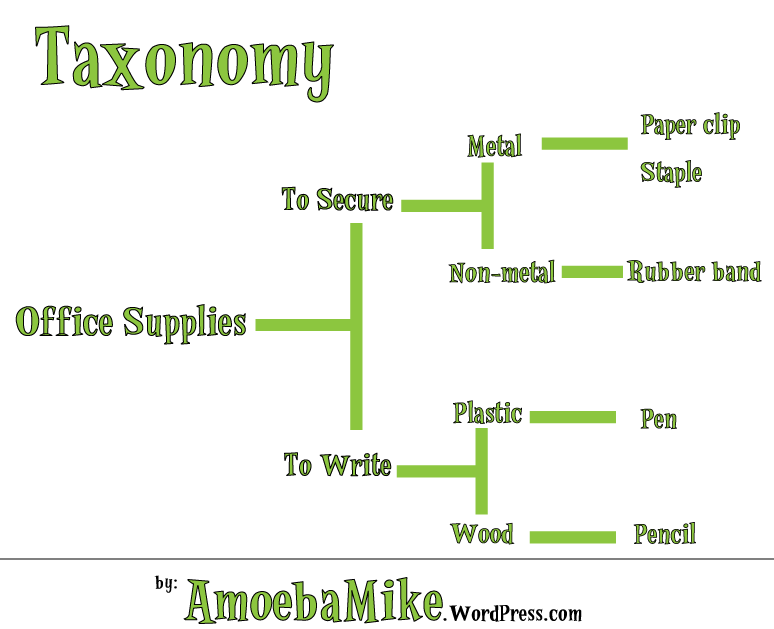

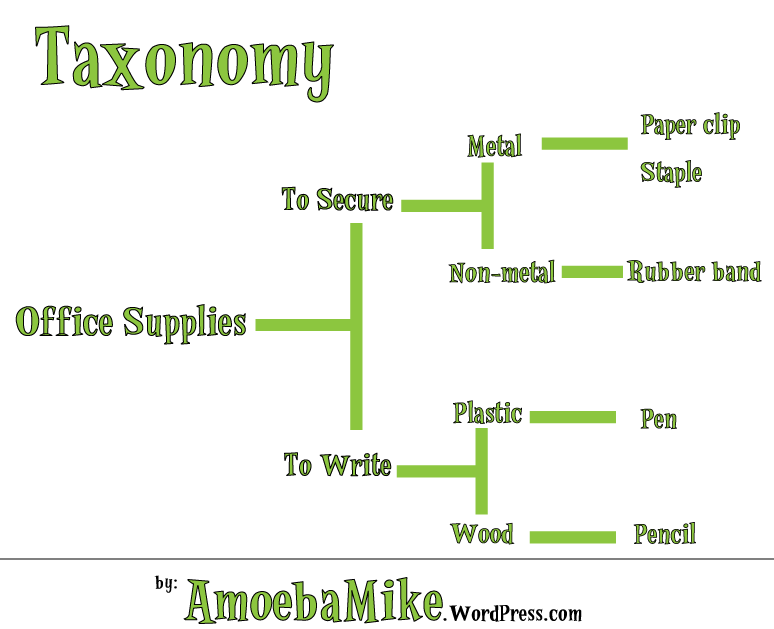

Motor Learning Taxonomy

A taxonomy is simply a classification system to describe specific things that relate to a more general idea. For example consider this taxonomy for the general idea of "office supplies"

Motor tasks can be classified from general to more specific using a taxonomy that differentiates the task using these four variable: environment, intertrial variability, and body stable/transport. Unlike the office supply example above, motor tasks are classified in a 2x2 matrix

Environment - described as open or closed

closed

- predictable

- objects do not move

open

- dynamic, unpredictable

- objects / others move

- surface and other movements within the environment are not within the control of the patient

- requires the ability to plan, anticipate, predict and respond to multiple changes while moving through space

- body stable: person is stationary

- body transport: person is moving through space or from one place to another

Intertrial variability - described as absent or present

- refers to changes in conditions of the task between attempts

- considered absent (no difference between attempts) or present (environment varies between attempts)

- higher the intertrial variability elicits adaptive responses to executing the motor skill

Body stable: person is stationary or,

Body transport: person is moving through space or from one place to another

ACTIVE LEARNING EXERCISE

Can you apply the motor learning taxonomy to a clinical situation? After watching this video example, use the CAN YOU HELP ME forum to escribe two to three functional activities that you observed in the clinic or have practiced in lab using lettering and numbering system in Gentile's Taxonomy (Table 11-4).

Support your classification with your rationale and I'll provide feedback on your effort.

1http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Motor_skill

Practice

Types of Feedback

- intrinsic - feedback is from the patient/client's body (sensorimotor and neuromuscular)

- extrinsic - feedback is from someone/something other than the patient (e.g., therapist, family member, judges score, referee call, etc.); may be referred to as augmentative if feedback is technology-driven.

- knowledge of performance and knowledge of result/outcome. Be sure to not overload the patient with feedback - allow time for processing and keep feedback into manageable chunks

Characteristics of Effective Feedback

- Emphasis on knowledge of performance.

- Specific - precise examples or behaviors

- Timing - appropriate to the level of the learner

- concurrent - given with manual or verbal cues at the same time the task is performed; used in initial stages of learning

- immediate, post-response - feedback is after each attempt; used in initial stages of learning; emphasis is on performance vs. learning (retention)

- delayed/summary - feedback is after a series of attempts; used as a progression to allow for self-assessment; higher correlation with learning and retention

- Frequency

- ranges from concurrent, intermittent, to summary to allow for self-correction of task performance

Motor Task Analysis

5+ minute audio file with some additional instruction for this page

Six Major Steps

- Identify the task(s) and specify the goals and sub goals

- Amass information concerning

- The action, including classification of the function of the action of movement

- The environment, including the influence of both direct and indirect conditions

- The mover/patient, including his/her characteristics, abilities, and whether the minimal prerequisite skills for success are present

- The prerequisite skills required of the client

- The expectations of outcome and movement outcomes

- Develop a strategy to make up for any deficits encountered in #2

- Plan the teaching/intervention strategy based on the preceding information concerning the individual-task-environment interaction

- plan an observational strategy for the intervention that can be used to:

- provide constructive feedback

- evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention strategy

- structure the environment for the intervention, taking into account a broad range of conditions for when the targeted skill may be needed

- Clarify the goals

- Effect the strategy

- Observe the performance of the mover

- Record what happened: what was the outcome and what was the approach and effect of the movement solution?

- Evaluate the observations

- Compare expectations and what happened

- Provide feedback based on the comparison above and assist the mover/learner in making decisions about the next encounter

- With the mover, plan the next intervention/task/encounter.

Essentials for Success during Patient Education for Motor Tasks

Ultimately, the patient/client's attitude regarding exercise and movement as a treatment for pain, weakness, stiffness, loss of function, etc., has the greatest influence on motor learning. A careful, thoughtful, exercise program will have little effect in carryover and learning if your patient is not committed to participating in an exercise treatment plan to reach his or her goals.

Tips to Maintain Patient Motivation

-

Maintain a positive, supportive relationship between the teacher/therapist and learner/patient/client

- Tailor the instruction to the individual's learning style (visual, verbal, kinesthetic), or providing multiple methods of instruction for the same activity

- Assess patient motivations and concerns, including whether or not they value exercise as a form of treatment for their condition; consider individual or cultural differences which may impact success when learning a new motor skill

- Consider patient impairment, functional limitation, and disabilities, particularly if there are challenges in attention, cognition, and memory

Tips to Build Rapport During Patient Education

- Be prepared: Have solid ideas and some options for your session before you start

- Match your patient: Provide an exercise opportunity in which your patient can be successful. Feedback is immediate and includes specific information about accuracy.

- Pace your patient: Provide multiple and regular exercise interventions which encourage he or she to work to the edge of their comfort zone; guidance and feedback from you is intermittent

- Lead your patient: Provide safe and progressive challenges which allow the activity to carry over to multiple environments. Patients can self-assess what they need to do differently and what they can do effectively with little to no input from you.

- Respect your patient: Consider environmental or cultural barriers which may impact their ability to complete the exercise/motor tasks in the manner you recommend; adapt approaches and programs to the individual while working toward PT goals.

- The "Compliment Sandwich". Congratulate your patient: try to end your treatment on a successful note. Include a positive - area for improvement- followed by another positive when concluding your treatment.

Role of the PTA

A PTA must consider each patient's functional level, motivation, endurance, treatment goals (including discharge plan), and environment when planning an intervention for improving function. PTAs are trained in functional task analysis. In short, PTAs make observations and comparisons and apply their knowledge of body movements, posture, balance, safety, cognition, and endurance to specific task requirements for the patient. PTAs select interventions within the plan of care to improve performance and retention of safe and effective movement strategies. In order for a PTA to be an effective patient educator, a PTA must apply motor learning principles and strategies during the treatment session and in planning treatment progressions.

Remember, patients need to have the opportunity to be successful, so they can internalize their performance and truly learn. Some basic considerations are:

- closed environments are easier than open.

- changing the set up or conditions between skill attempts makes the task more functional, but more difficult

- practicing activities where the body can be still is easier than practicing while asking your patient to move from one place/position to another

- quiet environments are less distracting (e.g., less "open") than noisy, active environments

- anything that requires fine motor control (e.g., use of hands to manipulate objects) will be more challenging than those which do not

- patient rapport influences motor learning

Tests Measures Used To Assess Motor Performance and Learning

PTAs use tests and measures to document the result of exercise instruction and functional mobility training. Motor performance and motor learning are assessed as the patient demonstrates the selected activity. For home exercise planning and assessment, PTAs should include some information which provides evidence that the patient understands (or does not understand) instructions and/or precautions for exercise. Parameters used to quantify and document progress with task-performance and motor learning include:

- amount: number of sets/reps of an exercise, increase or decrease in substitute or compensatory movement patterns

- duration: includes reaction time, time to initiate, or amount of sustained activity

- speed/rate: how fast/slow to start/end a task

- accuracy: includes number and type of errors (e.g., loss of balance) or external cues needed

- functional level of assist: includes patient ability to execute the skill with or without help; ranges from Dependent to Independent

- trials: number of attempts to complete or number of training sessions to reach outcome

- retention: ability to recall (e.g., repeat back the instructions, remembering to reference home exercise instructions, etc.) and repeat (demonstrate) skill independently

- Standardized outcome measures - task-specific standardized tests for gait, balance, function, etc. can be used to document varying levels of patient autonomy in activities of daily living

![]()

Serial task: a series of predictable steps to complete a task. Examples opening a locked door: key in lock, turn key, twist or press door handle. The series is important, because each subsequent step relies on correct completion of the preceeding step. For example a key in the lock will not open the door when the handle is pressed unless the key is turned first

Serial task: a series of predictable steps to complete a task. Examples opening a locked door: key in lock, turn key, twist or press door handle. The series is important, because each subsequent step relies on correct completion of the preceeding step. For example a key in the lock will not open the door when the handle is pressed unless the key is turned first