Stress Management and BioFeedback

PTA 103L Intro to Clinical Practice 2 Lab

"Stress is a non-specific response of the body for any demand to change" - Hans Selye

Stress is a physiological response to being alive. Our physiology is designed to maintain homeostasis (steady state) and a stress, either positive or negative, triggers a response in order to bring us back to a physiological neutral place. For the purposes of this lesson, we will focus on the effects of negative stress which is specific to external factors perceived as a threat. External factors include environmental and psychosocial factors.

Disease is the internal stress to human physiology. Impairments, functional limitations, and disabilities can become external stresses which further carry over into home, work, family, and sense of self. In order to facilitate patient/client recognition of the effects of external stresses on disablement, PTs and PTAs should practice self-awareness of stressors and stress management to maintain a therapeutic presence and avoid burnout.

This is a pre-lab activity to allow you to apply principles of stress management for biofeedback during laboratory activities and examination. By demonstrating understanding of stress management principles, students will:

The Stress Development Model theorizes there is a continuum between situational stressors and the development of disease. GI dysfunction, cardiovascular disorders, and acquired neuromuscular disorders have been linked to chronic stress.

Activation of our sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight) increases release of adrenaline with multiple physiological effects across body systems.

"Nobody can make you feel inferior without your consent" - Eleanor Roosevelt

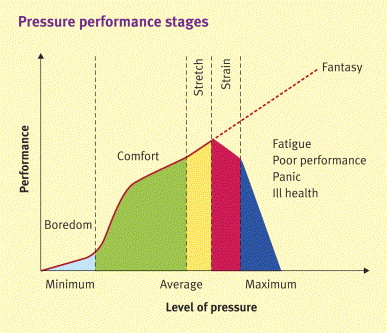

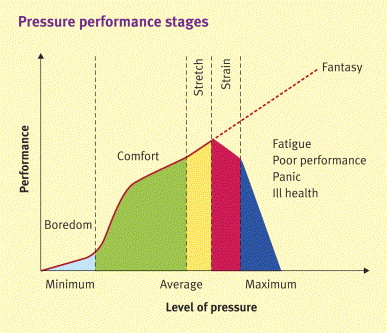

As noted in the Stress Development Model, stressors can lead to distress and then disease when the perception of the stress and the emotional response result in overactivation of the sympathetic nervous system. Eustress is the "good stress" which can provide motivation and drive to achieve and produce more in a given time frame. It the demand to achieve a certain result is perceived as a negative, then a eustress can progress into distress.

Stretch periods are ideally short periods of time where increased performance is required to achieve a result. If periods of stretch are long or uninterrupted, performance strain results and overall outcomes (performance or body functions) decline.

Neuro or Brain plasticity refers to organization and reorganization synaptic connections based on development, behavior and memory. Meditation, positive-self talk, movement based meditative practices (Tai Chi, yoga, etc), and reinforcement of control through biofeedback can all influence neuronal programming of perceptions and therefore modulate emotional responses to negative stress.

Health care workers are susceptible to burnout due to a generalized professional trait of empathy and a desire to help. Sources of burnout in health care providers include

Develop a healthy balance and growth in each of the following:

Health care providers who take care of themselves can be more successful in maintaining a therapeutic presence for self and others (including patients). You can serve as a mentor and a model for stress managment in peer and patient interactions and patient education.

Occupational therapy includes optimizing physical, cognitive and behavioral health in the workplace. Perspectives here provide a framework for how body systems (mental health) can influence activity, motivation, and work effectiveness.

Biofeedback is a process of electronically using information from the body to teach an individual to recognize what is going on inside the own brain, nervous system, and muscles. Biofeedback refers to any technique, be it visual, auditory, or kinesthetic, that uses instrumentation to give a person immediate and continuing signals on changes in a bodily function that he or she is not usually conscious of, such as fluctuations in blood pressure, brain wave activity, or muscle tension. Theoretically, and often in practice, information input enables the individual to learn to control the "involuntary" function.

Biofeedback is a training process in which the client becomes aware of and learns to selectively change physiological processes with the aid of an external monitor. A monitoring instrument is placed on the appropriate area of the body. The machine provides an initial readout. The client is instructed how to change the monitored process, and as change occurs, the machine "feeds back" that information. By mentally changing a biological function, the client learns to gain control over it. In time, the client learns to control the process without needing an assist from the instrument. This is known as the "self-efficacy" model. Improved motor performance through motor learning (feedback and knowledge of results) is one goal of biofeedback.

Muscle tension, pulse rate, blood pressure, skin temperature, and electromyography (EMG) and electroencephalography (EEG) readings are some of the physiological processes that can be consciously modified with biofeedback.

Movement, whole body balance, and joint displacement can also serve as sources of biofeedback

volitional movement, neuromuscular re-education

volitional movement, neuromuscular re-education

Energy conservation techniques provide the easiest way to decrease the work of muscles without loss of function. Analysis of all activities by type, time, distance, and intensity is valuable in designing interventions. Such an inventory forms the basis for setting priorities and determining where and how individuals wish to use their limited neuromuscular capacity.

Questions addressed include the following:

Particular attention should focus on activities that produce fatigue and pain. Specific suggestions may address breaking tasks into subtasks, environmental adaptations such as work height and locations, using frequent rest breaks during activities, and use of adaptive or ergonomic equipment.

Psychological considerations play a major role in designing an acceptable and appropriate management plan that will encourage compliance. Lifestyle modifications may not be favorably viewed by some individuals who have "conquered" the disease and pushed themselves to be independent. Prescription of interventions that are perceived to be "radical" should be done with sensitivity and caution. The rationale for interventions should be carefully considered in light of the client's current functional status and goals. Introduction of orthoses, assistive devices, and mobility modifications is often difficult for the individuals with congenital or childhood onset of disease to accept, given the long, arduous effort expended over years to avoid such devices.

Home management activities may be divided into two components: light home management and heavy home management. Light home management includes money management, preparing a snack in the kitchen, laundry, and making the bed. Heavy home management includes grocery shopping, preparing a complex meal in the kitchen, dusting, and vacuuming. The clinician should discuss the role the client would like to assume at home. The client may want to resume previous home management roles or want to discuss changing roles with a family member or caregiver to have energy for other skills.

Reduction of muscular overuse and fatigue may be accomplished with lightweight splints and braces, adaptive equipment, walkers, or crutches.

As with every intervention, a thorough explanation of the specific rationale and goals for the intervention will not only be helpful in gaining the client's trust but will also improve compliance. Rationale for orthotic use includes preventing falls and potential fractures, limiting joint motion and preventing pain, restoring weight bearing on the weaker extremity to decrease the work of the less affected leg in locomotion, improving posture and decreasing back pain, and decreasing energy expenditure.

Thoughtful consideration for the appropriateness of orthosis or assistive devices is critical; such devices should not be haphazardly prescribed or given as the only intervention of choice. They should be prescribed cautiously. Ineffective and inappropriate use of such devices will lead to malalignments, ineffective movement strategies, and postures that will cause more harm. Therapists should carefully evaluate the functions that may be lost or gained and the emotional and physical cost of their use.