Shoulder dysfunction: Conservative management (non-operative)

Humeral fractures

are treated with casting (closed reduction) or hardware (open-reduction/external fixation). ROM to prevent contractures are the primary component of early rehabilitation. Progressive strengthening and stretching for improving post-fracture weakness and atrophy will depend on integrity of bone tissue during fracture healing. A significant complication of humeral fracture is avascular necrosis of the humeral head. Indications for joint replacement secondary to avascular necrosis are discussed further in the section on Surgical Management.

Scapula fracture

Incidence of scapular fracture is highly associated with trauma, therefore, patients will often present with other fractures, glenohumeral dislocations, pneumothorax, and/or neurovascular injuries. Scapular body fractures are the most common scapular fracture and are generally treated non-operatively. As pain and swelling subside (2-3 weeks of immobilization), patients may progress from isometric to active exercises.

Glenohumeral Hypomobility

|

Presentation |

Associated conditions/etiology |

Clinical signs and symptoms |

Impairments |

Functional Limitations |

|

Joint is stiff, motion and muscle function is limited |

OA/RA, trauma, immobilization, idiopathic adhesive capsulitis |

limited external rotation>abduction, pain, limited functional motion |

Pain during sleep/lying, pain and limited motion, scapular compensation, decreased arm swing during gait |

Difficulty dressing, grooming, reaching and lifting; difficulty reaching behind back |

Joint stiffness and pain can result from overuse of contractile and non-contractile structures. Arthritic changes to the humeral head, glenoid fossa, acromion, or sternum can all impact function. Joint stiffness can evolve during or following hospitalization due to illness or decline in function. Patients who are confined to bed or have extended periods of compromised cardiopulmonary endurance may develop stiff and painful shoulders in as little as 1-2 days. PTAs play a significant role in patient, family, and staff education in correct ROM techniques for the shoulder for contracture prevention and management.

Adhesive capsulitis ("frozen shoulder") has a greater incidence in women (40-60 years old) and may be associated with diabetes and other chronic inflammatory conditions. Significant functional limitations can present in as little as 24 hours following initial symptoms. Depending on pain, length of symptoms, and functional limitations, patients may undergo manipulation under anesthesia to manually break through adhesions in external rotation and abduction without an inhibitory guarding response. PROM immediately following manipulation and patient education in ROM techniques follows this procedure.

During the maximum protection phase, PTs will use mid-range joint mobilizations to increase mobility without increasing pain.

Stages of Adhesive Capsulitis

|

Acute "freezing" (10 wks to 3 months) |

Subacute "frozen" ( from 4 months to 12 months) |

Chronic "thawing" (2 months to 24 months) |

|

Patient presents with pain at rest and with shoulder motion Controlled pain-free motion and interventions to promote relaxation of muscle guarding of the glenohumeral joint, cervical area, and scapulothoracic muscles Scapula stabilization exercises with correct technique Joint mobilization

Frequent ROM (3-5 x) during day and stretching in end-range

Modalities for pain relief: ice, US, estim |

Patients present with pain only with shoulder motions, scapula compensation with movement, and deltoid atrophy.

Exercise to restore glenohumeral and scapulothoracic motion and prevent scapula substitution; progressive strengthening of deltoid, scapula, rotator cuff and upper arm

Submaximal closed chain isometric shoulder strengthening |

Patients present with little to no pain, joint stiffness, and decreased muscular endurance

PT to Increase strength, endurance and functional use; continue self-stretching |

Precautions with Adhesive Capsulitis: Therapy is too aggressive if the patient reports increased pain or joint irritability

Contraindications with Adhesive Capsulitis: Stretching into end-range when there are signs and symptoms of active inflammation

Glenohumeral Hypermobility

Excessive motion at the glenohumeral joint can increase stress to bone, contractile and non-contractile tissue resulting in increased degeneration, instability with subluxation/dislocation, and overuse of static and dynamic stabilizers (sprain, tendinitis, etc.). Conditions which may result in hypermobility include:

- History of trauma (fall on outstretched hand)

- Generalized laxity (inherited, connective tissue disorders, history of previous dislocation)

- Hemiparesis

- loss of neuromuscular control results in an unopposed traction force on the upper extremity when upright. This can become quite painful as the nerve are traction and soft tissue structures are overstretched. A hemi-sling may be used permanently or temporarily for joint and soft tissue protection when there is neurological paresis or paralysis of the upper extremity

https://www.ncmedical.com/item_669.html

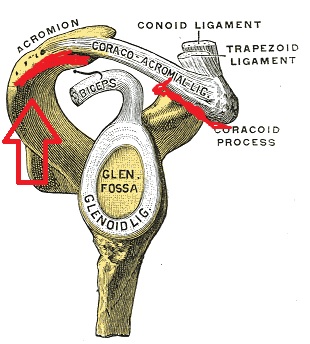

Non-traumatic Acromioclavicular (AC) Joint Dysfunction

Non-traumatic AC joint dysfunction is common in adults over 40. Correction of postural stressors and muscle imbalances can prevent or minimize progression of arthritis. Weight lifters and individuals who repetitively load the upper extremities are more likely to experience dysfunction in these smaller shoulder complex joints

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ec/Gray328.png

|

Overuse |

Subluxation or Dislocation of AC jt |

Hypomobility |

Impairments |

Functional Limitations |

|

Associated with repeated diagonal extension-adduction-internal rotation (tennis, volleyball) and repetitive motion at waist level |

Associated with direct fall onto shoulder and fall on outstretched arm May include partial or complete tear of supporting ligaments |

Associated with poor posture, especially scapular depression and retraction; OA common in AC joint after age 40 |

Localized pain; pain with shoulder elevation, horizontal adduction or abduction, hypomobility, neurovascular dysfunction |

Difficulty with repetitive motion forward/backward; limited participation in volley sports; decreased overhead reaching |

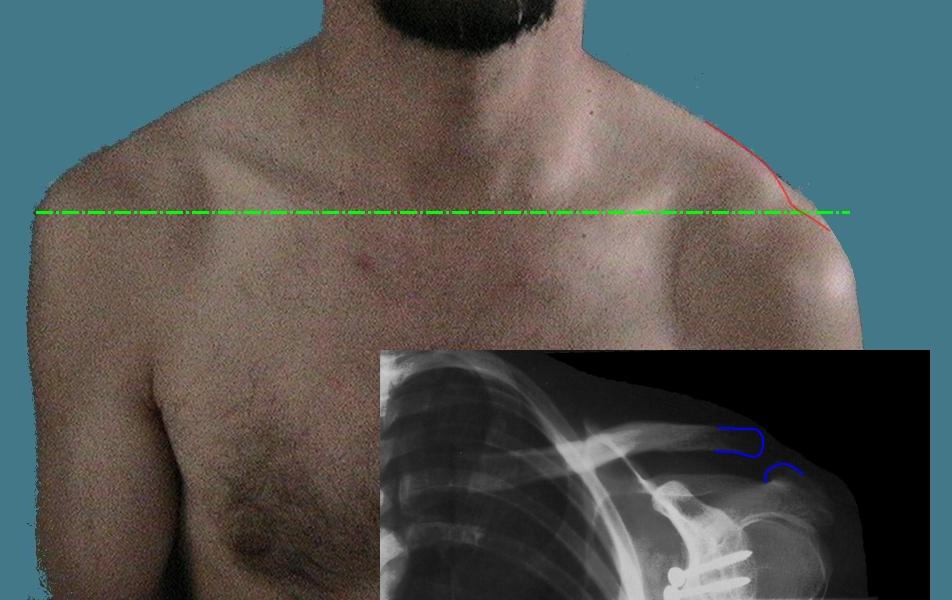

AC joint subluxations and dislocations can be graded by MDs and radiologists based on the amount of ligamentous damage. When reviewing the medical record, you may see reference to Grade I, II or III AC sprain. Higher grade sprains are less stable. AC joint disruption is also referred to as "shoulder separation"

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/9e/Luxation_acromioclaviculaire.jpeg

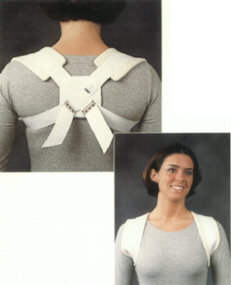

Grades II and III A-C sprain benefit from a harness or sling for 3-6 weeks so that the torn ligaments can heal through superior pressure to clavicle. Clavicle braces are also prescribed following clavicle fracture

http://heritagemedical.typepad.com/heritage_medical/shoulder/

http://heritagemedical.typepad.com/heritage_medical/shoulder/

Subacromial Impingement Syndromes

Video is approximately 3 minutes

- supraspinatus tendon is the most common structure involved in impingement, followed by infraspinatus, then subscapularis

- may also present with inflammation of bursae (primarily subacromial bursa)

- incidence is influenced by age of the patient and shape of the acromion (flat, curved, or hooked)

- condition is associated with:

- posterior capsule tightness

- decreased control of rotator cuff muscles

- faculty scapulothoracic posture

- tear of structure in suprahumeral space

- tendinitis (see Special tests)

- sports-specific activities (racquet sports)

- causes

- overuse

- trauma (fall on out-stretched hand)

- exercise and movement form

- muscle imbalance (tightness, over-development) and weakness; age-related changes

- stages of impingement (Neer' stages) are based on patient age, pain level, and the degree of involvement of rotator cuff structures

- Stage I: edema and hemorrhage in subacromial space, typically age 25 or less, pain with abduction > 90 degrees; reversible lesion

- Stage II: fibrotic changes (RTC tendons, long head biceps, bursae); typically age 25-40, increased pain and pain at night with sidelying; irreversible lesion

- Stage III: includes some RTC tear with chronic pain; generally includes weakness and atrophy of surrounding RTC structures; irreversible lesion

- largely characterized by a painful arc of motion between 60 and 120 degrees of abduction, difficulty with overhead reach and lifting, difficulty with dressing and ADLs.

- Special tests will help identify involved structures: palpation at musculotendinous junction of RTC muscles and associated structures should also be noted on PT evaluation

- Positive (+) Impingement sign (aka 'Hawkins test'; pain with flexion to 90 degrees plus internal rotation) = supraspinatus tendinitis (Video is approximately 1.5 minutes)

- Positive (+) Speed's test (resisted forearm supination while shoulder is flexing) = long head biceps tendinitis (Video is approximately 2 minutes)

- Positive (+) Apprehension sign (patient refusal/avoidance of combined shoulder elevation, abduction, and ER) = GH anterior (Video is approximately 2 minutes)

- instability

- Positive (+) Anterior/Posterior drawer indicates anterior/posterior GH joint instability

- Positive (+) Crossed arm adduction; pain may indicate AC joint involvement

- Positive (+) Drop arm test; patients is unable to maintain isometric hold of 30 degrees abduction against gravity; indicates failure of supraspinatus (Video is approximately 2 minutes)

- may be treated with cortisone injection(s) to decrease inflammation in subacromial space; modalities may be effective during acute tissue healing phases for pain control and edema management

- progression to overhead motion is allowed once pain-free ROM (full or functional) is restored

- PT interventions are based on tissue healing stages with an emphasis on maintaining as much motion in joints above and below the shoulder and continuing non-painful motions or activities involving the upper extremity

Impingement Syndrome Presentation

Impingement typically presents as subacromial impingement; however impingement can also occur between the glenoid, the glenoid labrum and the suprapinatus and infraspinatus

|

Associated condition/etiology |

Clinical s/sxs |

Impairments |

Functional Limitations |

Goals and Treatment(s) |

|

Overuse from repetitive motion (overhead, throwing) Overuse from repetitive eccentric loading (racquet sports, volleyball, etc.) History of joint stiffness, OA, acromion shape precursors History of fall on outstretched hand History of MVA (holding steering wheel at impact) Poor posture (thoracic kyphosis, ant-posterior muscle length-tension imbalances Poor glenohumeral joint stability |

Painful arc of motion (usually 60-120 degrees of abduction) Pain with sidelying, reaching overhead, reaching behind back, lifting Point tenderness at musculotendinous junction of involved structure

|

Pain, muscle guarding, posture, weakness, joint dysfunction |

Decreased lifting, pushing, pulling, overhead reaching, dressing, grooming |

Control pain and swelling, increase and maintain maximum pain-free range of motion, modify activities/ADLs, increase scapular control and stabilization, restore strength and timing of scapular and RTC during AROM, increase muscular endurance and postural control, progressive return to functional and sports-specific activities

Ice, NSAIDS, Iontophoresis, ultrasound, progressive strengthening, joint mobilization, stretching, postural education and re-education |

Shoulder Dislocations

- most often occurs due to trauma or history of previous shoulder dislocation

- source of secondary impingement due to poor control of superior motion of humeral head into subacromial space during overhead shoulder motion

- instability can be unidirectional or multidirectional (anterior, inferior, posterior) and may or may not involve rotator cuff tear

- anterior dislocation is most common: blow to shoulder or arm while positioned in combined shoulder external rotation and abduction

- posterior dislocation may occur following fall on outstretched hand

- may also involve damage to rotator cuff, labrum, humeral head, glenohumeral ligaments, and neurovascular structures

- Bankhart lesion = avulsion tear of anterior capsule at the anterior glenoid labrum

- Hill-Sachs = posterior-lateral humeral head compression fracture resulting from anterior instability

- Axillary or brachial plexopathy with sensorimotor changes from compression or over-stretch

- Patients with a T traumatic U unidirectional injury and a B an kart lesion frequently require S surgery (TUBS). Patients with A traumatic M multidirectional B bilateral instability respond well to R habilitation, but occasionally require anI nferior capsular shift surgical procedure (AMBRI).

- Immobilization for short term (1-2 weeks) is recommended to allow the capsular structures to stiffness post-injury; patient continues with distal UE use and isometric exercise in 0 degrees flexion and pain-free intensity.

- Extension greater than 0 degrees is contraindicated until capsule is stabilized; caution with external rotation in positions greater than 55 degrees of shoulder abduction; no combined end-range abduction-external rotation motion until 3+ months post immobilization

- Early exercises are gravity assisted pendulum motions, isometric with progressing through limited range. During progressive strengthening and return to function, modify exercises to protect anterior capsule: overhead press and chest press activities should be modified to limit abduction to the scapular plane

During the initial immobilization, the PT documents all limitations of specific joint motion. Each limitation is addressed as part of the rehabilitation program. However, if the PTA recognizes delayed restoration of motion, reduced motion, or increased pain during the rehabilitation program, then he or she immediately must communicate this to the PT.