Spine: Kinesthetic, Mobility and Flexibilty Considerations

PTA 104 Orthopedic Dysfunctions

In your Applied Kinesiology 2 course (PTA 133L), you practiced methods for measuring ROM and strength in the spine. Core stabilization concepts were introduced during Week 1 in PTA 133 as you learned about the structure and function of the thoracic and lumbar spine. Your study of kinesiology has reinforced the meaning of basic, intermediate, and advanced stretching and strengthening techniques as it relates to normal muscle function. By now, you have spent some time working on your observation and assessment skills in determining factors which may influence postural tendencies.

In PTA 104 and PTA 104L, we expand on the skilled exercise interventions by carefully selecting and applying therapeutic exercise in order to facilitate optimal tissue healing and return to function. Exercise prescription in orthopedic conditions is specific to a pathological condition resulting in an impairment based movement syndrome. Exercises applied inappropriately or indiscriminately can result in further damage to vulnerable or healing structures. PTAs are trained to recognize when exercise progression is appropriate, when to modify and exercise or movement-based approach and when to refer back to the PT should symptoms indicate a regression or change in condition.

The objectives for all content included in Chapter 16 of Kisner and Colby is included in this interactive lecture.

Exercises all patients should learn regardless of their functional level (Kisner & Colby, p. 440)

Based on

Kinesthetic Training: patient education on safe spinal motions with integration and application to activities of daily living

Stabilization Training: accessing and contracting muscles which provide spinal stability during gross motion

Functional Training: applying principles of body mechanics during everyday activities

Healing continuum and expectations for recovery

Patient-centered goals with direct patient engagement during treatment

Includes instruction in prevention

Therapeutic exercises are based on integrating pathology, tissue healing processes, and patient symptoms and limitations. Table 16-2 in your K&C text (p. 442) provides an excellent summary of general exercise applications based on the stage of recovery. This lecture covers the basic interventions, and subsequent lectures will address stabilization and functional progressions.

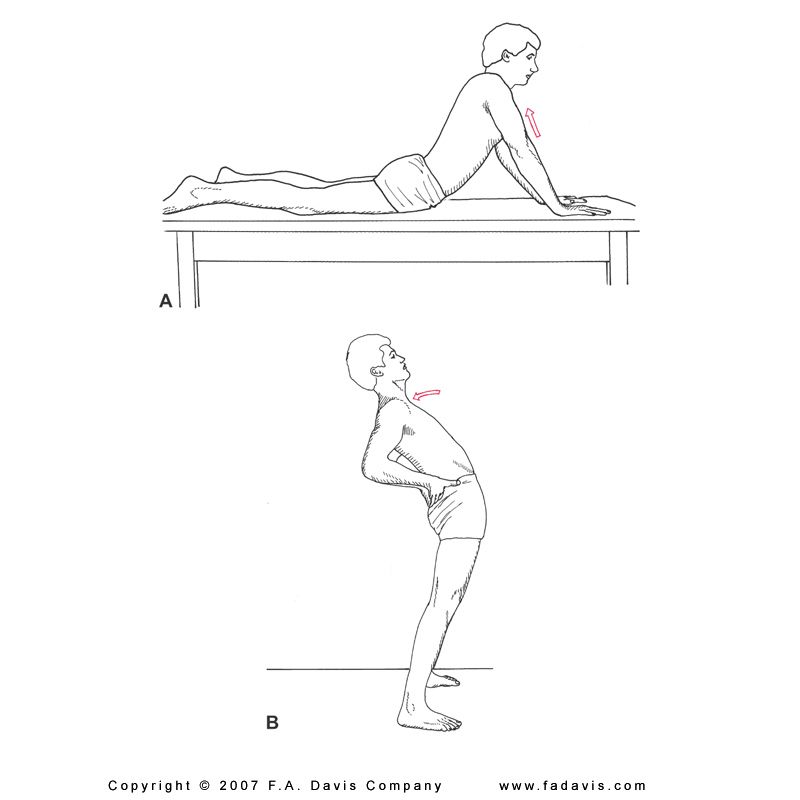

Position of bias = position of symptom relief; a.k.a., resting position

Neutral spine = mid-range of motion in all planes

Emphasis is on bringing the patient's attention to what feels worse/ better and then training them to find and use those positions of relief

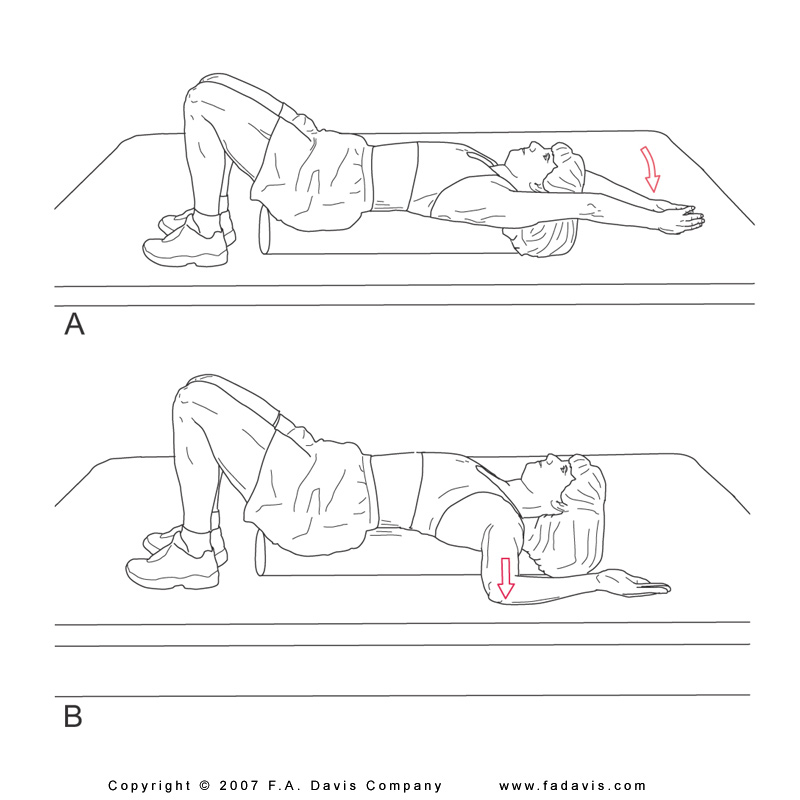

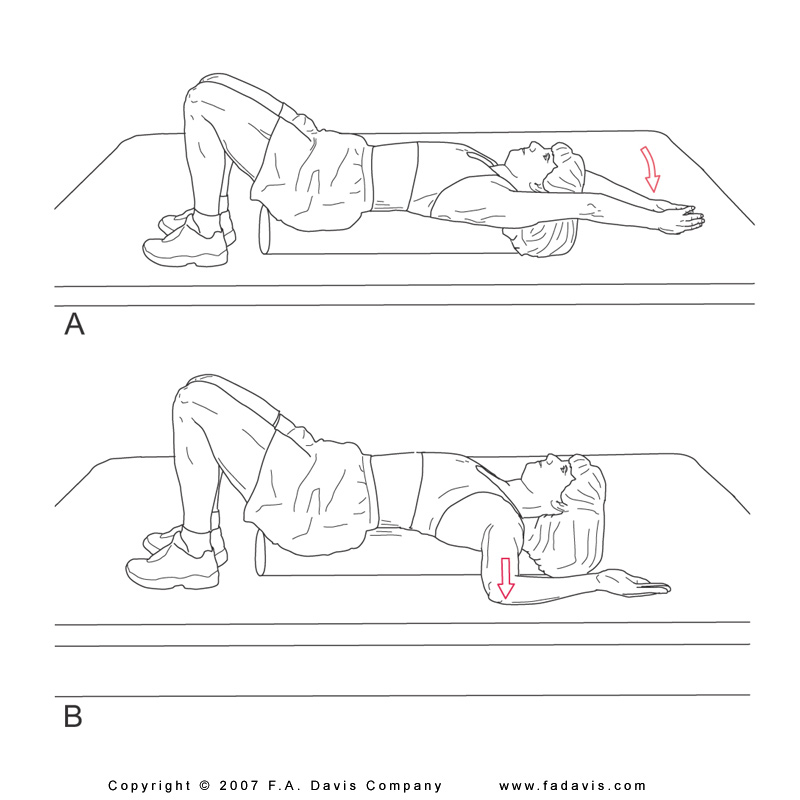

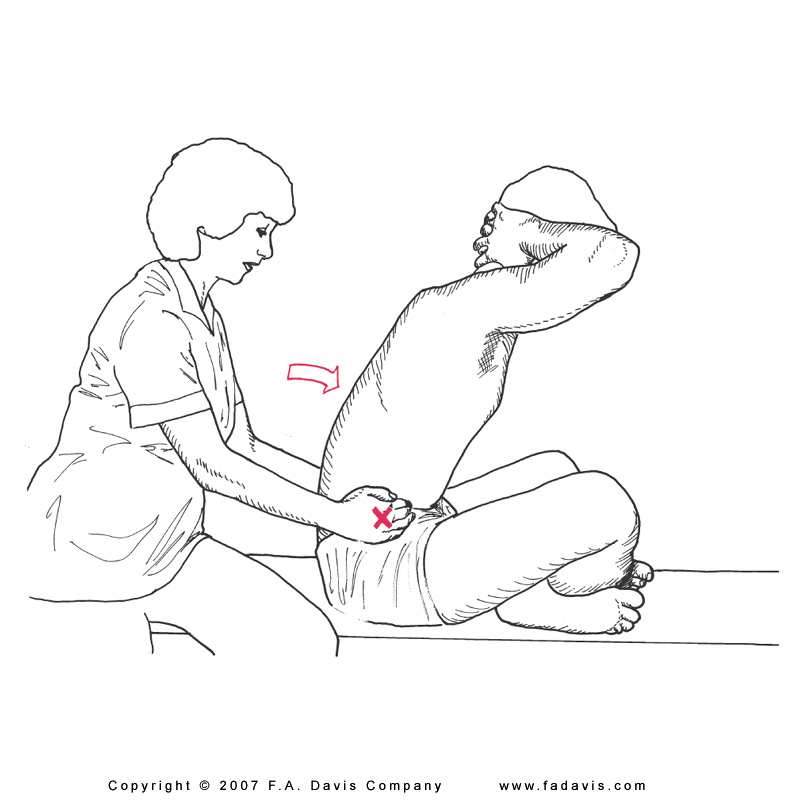

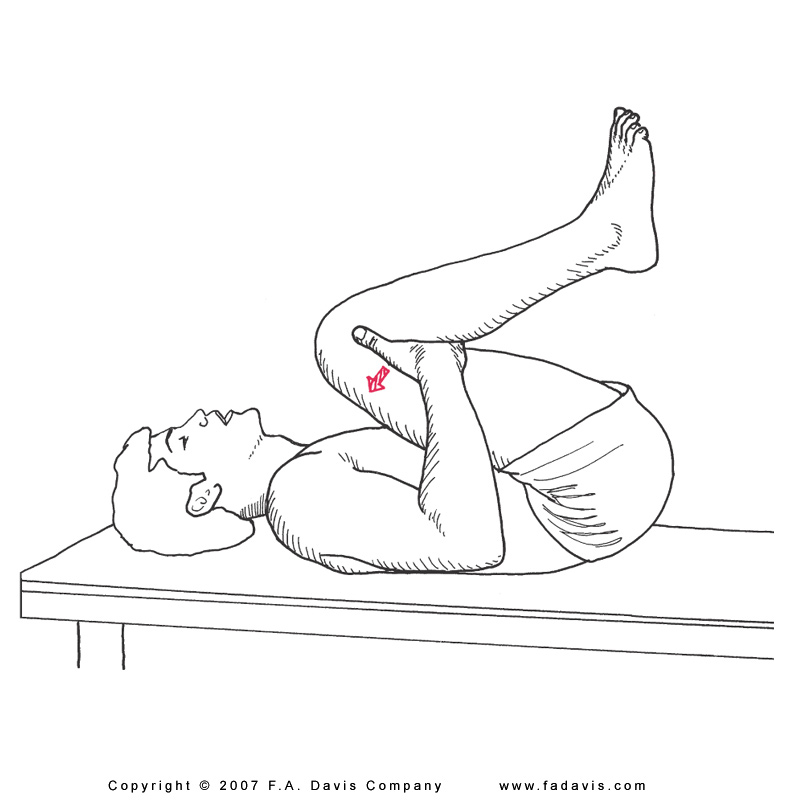

Facilitated passive ROM with verbal cues with transition to active-assisted and active range of motion. Patient should be positioned according to symptom tolerance (WB vs. non-WB). Supine positioning when first learning these techniques is recommended.

Passive positioning into posterior tilt (hooklying) or anterior tilt ( gentle long leg pull in supine); or with towel prop. Hook-lying is ideal for initiating kinesthetic training in pelvic tilt motions.

Progress to active positioning by instruction in pelvic tilt, moving through safe range and finding position of ease

limbs moving away from trunk = leads to spinal extension

limbs moving toward trunk = leads to spinal flexion

Bringing patient's attention to the effect of limb

Integrate motions into functional activities: rolling, sit to stand, bending, etc.,

Use of visual (mirror), verbal, and tactile cues for engaging core muscle and controlling dynamic movements to decrease incidence of painful symptoms

Stretching principles

may be contraindicated in inflamed tissue, however; assisted or positional stretching may be used to decrease tissue tension and allow patient to place spine in positions which decrease stress to involved structures.

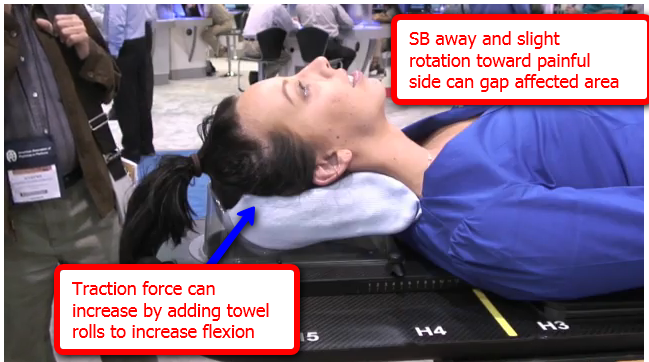

Traction forces are stretching forces which may be used to decompress inflamed nerve root structures, thus decreasing pain

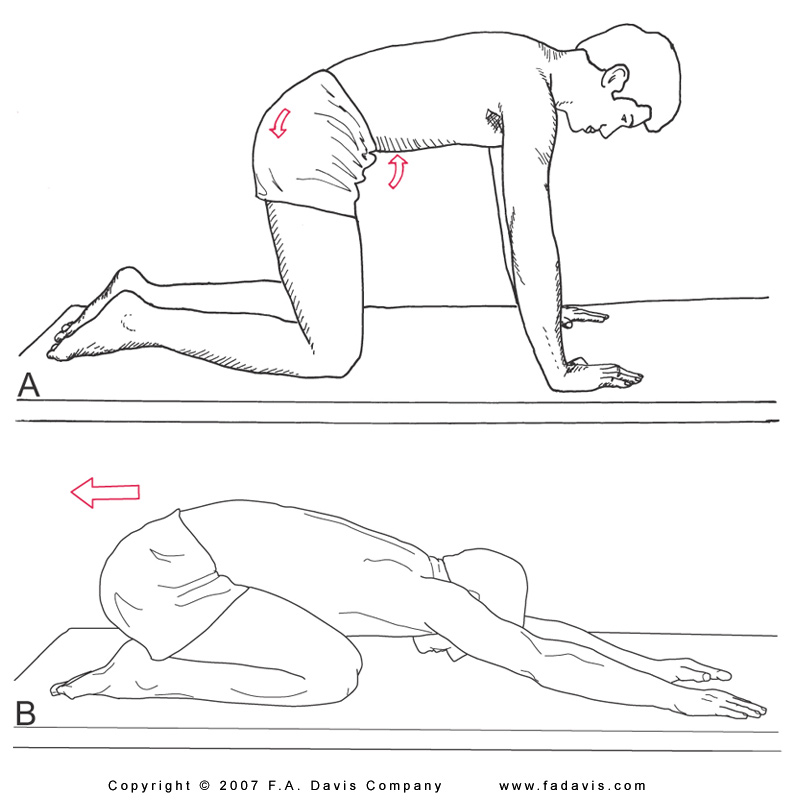

The procedures to position patients and perform spinal stretches are described in detail in Chapter 16 of Kisner and Colby. We have added some additional clinical considerations when selecting the stretching exercise. We recommend that you trial and experience each of the stretches listed in order to reinforce your understanding of the procedures and the intended effect on targeted tissues/structures.

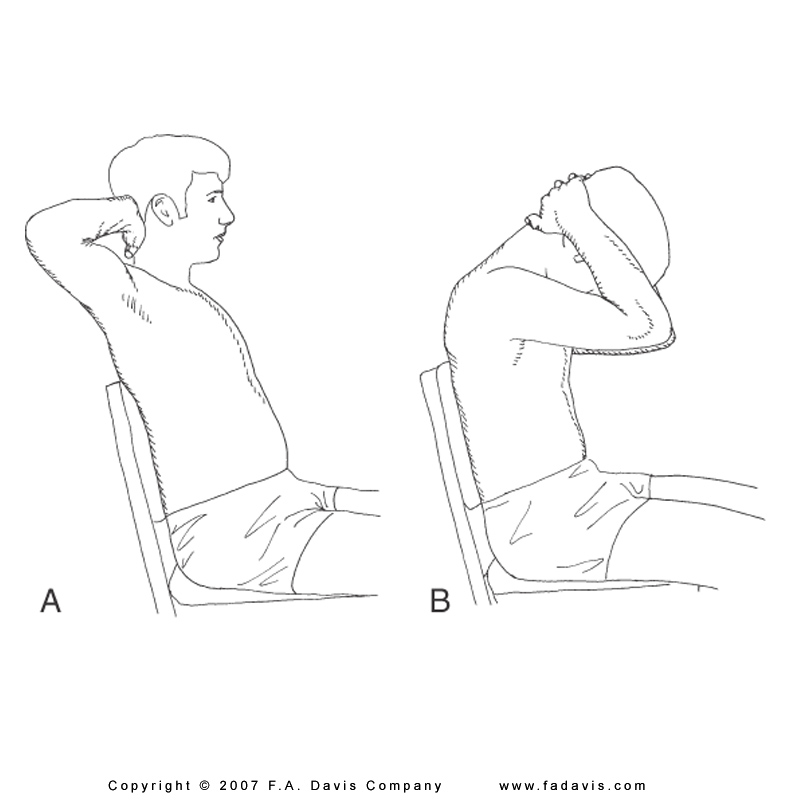

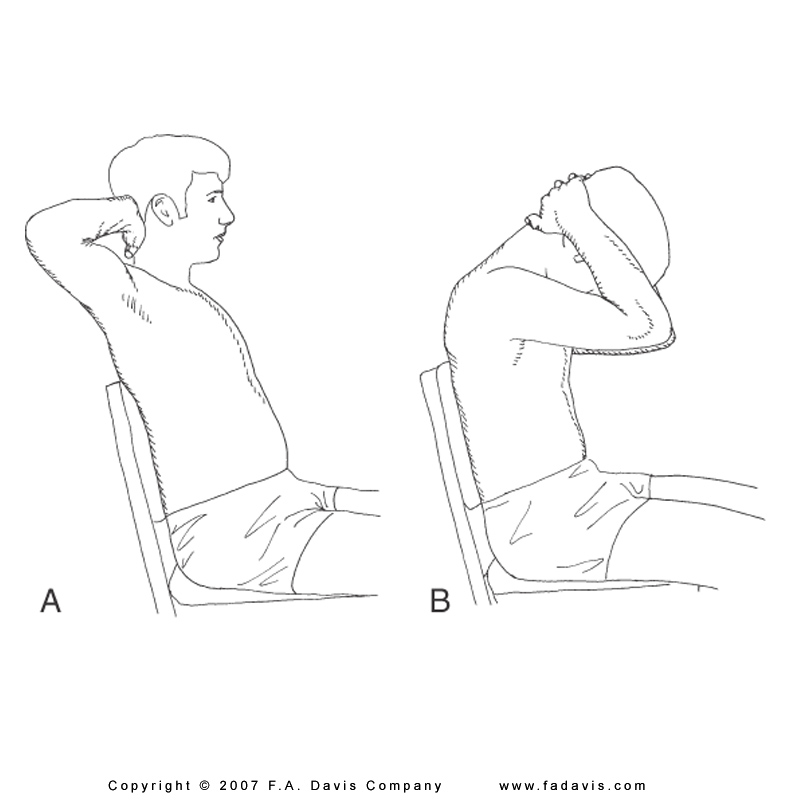

In your text, the authors describe a self-stretch in standing. Try a self-stretch while sitting in a chair. Reach down for the underside of the chair and hold. This will stabilize the distal end and prevent scapular elevation or side bending compensation during stretching

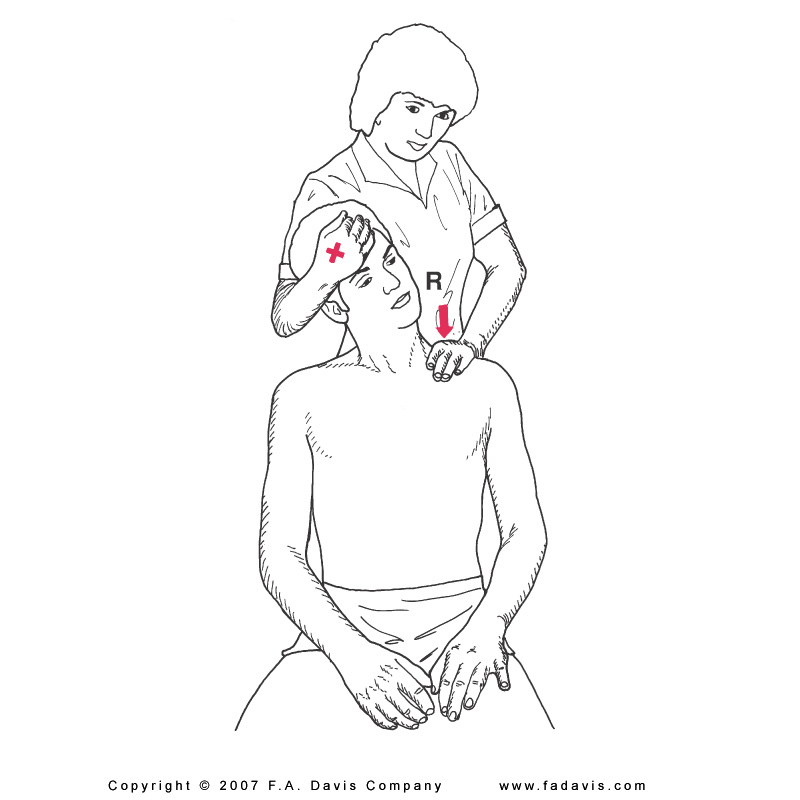

Review the procedures outlined on p. 445-446 in K & C. Recall from kinesiology that cervical flexion is a primary function of the OA joint. By integrating eye motions into the assisted stretching activity, you can use principles of contract-relax and increase patient awareness of how eye position and eye gaze influencse cervical ROM.

Forward head posture is largely driven by muscle imbalances. Think of the number of activities in a day which require the arms to be held in front of the trunk. Think of the amount of hours spent sitting and typing, reading, etc. Lengthening of posterior structures from postural habits or lack of use can lead to a resultant shortening in the anterior trunk.

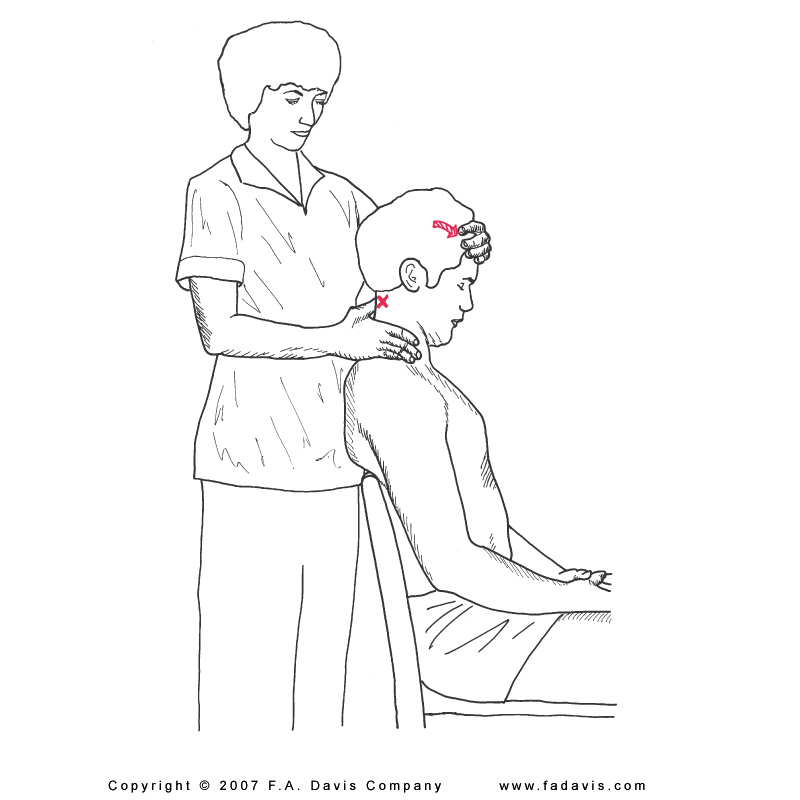

Manual traction is described and illustrated on p. 446 in K&C and is also depicted in your Review for Traction Skill Check resource in PTA 104L.

Cervical traction can be provided positionally. The image below illustrates passive positioning of the cervical spine in their bias position. A therapist can educate the patient on the use of pillows or towel rolls and positions of relief through applied kinesiology in the spine.

Self-cervical traction can be performed with the patient in sitting. Patients can either assume upright sitting or sitting in slight flexion with elbows on knees and pulling on the occiput (through laced fingers) in a cephalad direction.

Contract relax approaches can be used effectively in the spine to decrease muscle guarding through reflexive inhibition

Monitor for any increases in peripheralization: pain, numbness, or tingling sensations should not intensify or radiate down the extremity with assisted and/or self-stretching.

Your K&C text provides several options for assisted and self-stretching of the lumbar musculature

Perform each of the lumbar stretches as instructed in your text. Ask a classmate or family member to provide the illustrated pelvic stabilization force. What do you notice? What patient-specific limitations might interfere with a comfortable stretch position?

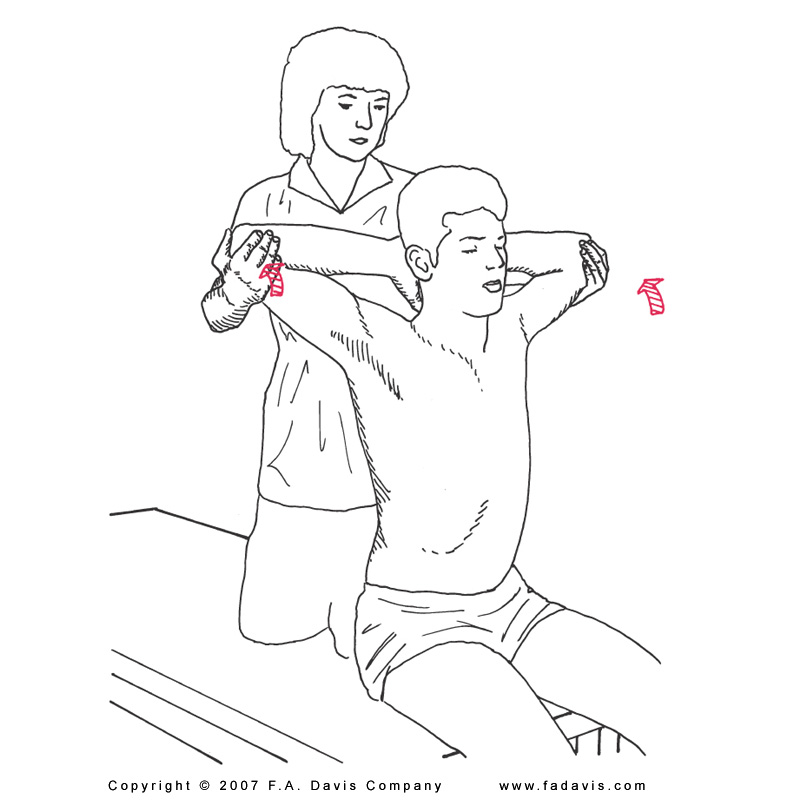

Note that your text emphasizes the importance of stabilizing either the pelvis or thorax in order to optimize the stretch. Family members can also be trained to assist with

lateral trunk stretching.

Be sure to integrate breathing techniques to use rib cage mechanics in adding to the stretch. Additional lateral trunk stretches are described and illustrated in K&C on p. 449-450.

Use of a traction table is discussed in the PTA 104L Review for Traction Skill Check resource. Note the benefits of a split table as it relates to the coefficient of friction.

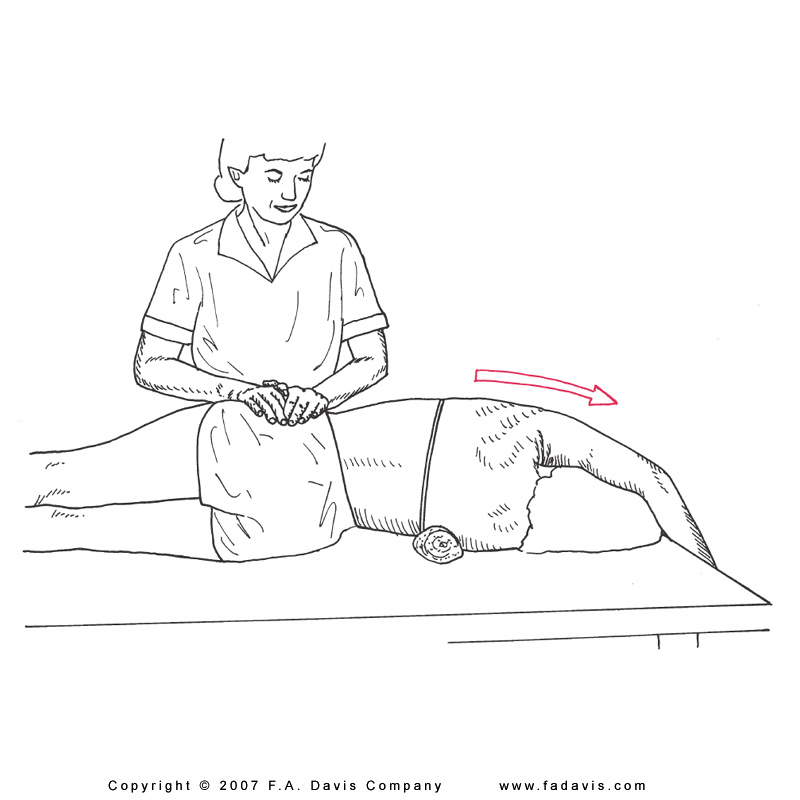

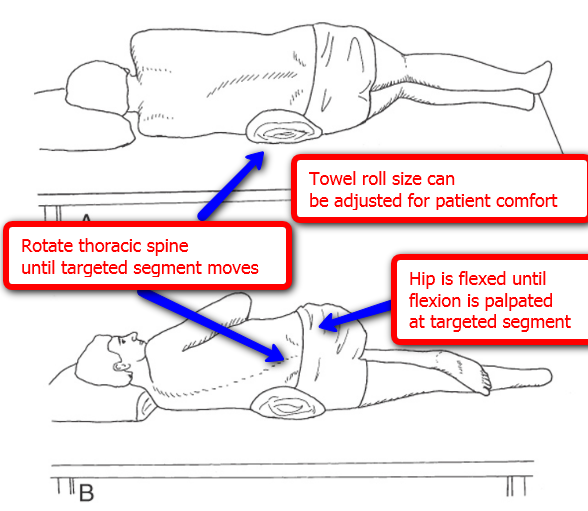

1. Position yourself in sidelying. Note the amount of side bending in the lumbar spine and weight bearing pressure in the contralateral shoulder and greater trochanter.

2. Repeat with hand towel rolled into a cylinder and placed under waistline

3. Repeat with standard bath towel rolled into a cylinder and placed under waistline.

What are the differences in your comfort level? If you needed to be in a sidelying position on a treatment table for greater than 5 minutes, which of the three options would you choose? Compare your findings with classmates and note differences in preferred positioning.