Interventions for the Spine

PTA 104 Ortho Dysfunctions

The following information is used for instructional purposes for students enrolled in the Physical Therapist Assistant Program at Lane Community College. It is not intended for commercial use or distribution for commercial purposes. It is not intended to serve as medical advice or treatment. Contact howardc@lanecc.edu for permissions.

Note: There are approximately 20 minutes of screencasts with the instructor as part of this interactive lecture.

Time to complete suggested active-learning activities and self-checks within the lecture is estimated at 1-1.5 hours

Video approximately 13 minutes

In your Applied Kinesiology 2 course (PTA 133L), you practiced methods for measuring ROM and strength in the spine. Core stabilization concepts were introduced during Week 1 in PTA 133 as you learned about the structure and function of the thoracic and lumbar spine. Your study of Kinesiology has reinforced the meaning of basic, intermediate, and advanced stretching and strengthening techniques as it relates to normal muscle function. By now, you have spent some time working on your observation and assessment skills in determining factors which may influence postural tendencies.

In PTA 104 and PTA 104L, we expand on the skilled exercise interventions by carefully selecting and applying therapeutic exercise in order to facilitate optimal tissue healing and return to function. Exercise prescription in orthopedic conditions is specific to a pathological condition resulting in an impairment based movement syndrome. Exercises applied inappropriately or indiscriminately can result in further damage to vulnerable or healing structures. PTAs are trained to recognize when exercise progression is appropriate, when to modify and exercise or movement-based approach and when to refer back to the PT should symptoms indicate a regression or change in condition.

Functional Components of the Spine

This table adds subcategories to the "acute" and "chronic" stages of recovery. Patients present in the clinic with acute findings, such as high pain levels and restricted motion, without a known source of inflammation or trauma. It also includes some general functional limitations that patients present with during these stages.

By understanding typical functional limitations along this continuum, a PTA can help educate patients on what is expected in a typical course of treatment and rehabilitation. When patients understand why they need to progress or limit activity and the expected goal of these behaviors, they are more likely to adhere to a home exercise and activity program.

Additionally, the "chronic" stage can refer to a patient who is seeing a physical therapist for the first time, and has complained of spine and related pain and limited function over a longer period of time. These patients may be referred to as experiencing "persistent" pain. Patients who experience persistent pain may present as "acute without signs and symptoms of inflammation". When the physical therapist and treatment team have determined that the spine pain and related functional loss is relatively unresponsive to conservative and other interventions, the physical therapy plan of care typically focuses on management strategies. Management strategies include, but are not limited to: breathing, pacing and prioritizing, a range of exercises (from gentle motions to resistance training), mindfulness and meditation, topical analegesics, heat, and sleep education).

|

Healing Stage |

Rehab Stage |

Duration |

Pain |

Functional Limitations

|

Goal |

|

Acute and inflamed |

Early training and protection phase |

<2 weeks |

constant; cardinal signs of inflammation; no positional relief |

Limited in all mobility and basic self-care

|

Control symptoms; progressive return to ADLs |

|

Acute w/o s/sx inflammation |

Progress to Basic Training - Controlled Motion |

2-4 weeks |

intermittent; mechanical; sxs of nerve irritability; impairment classification emerges |

Standing limited to less than 15 min; sitting limited to less than 30 min; walking limited to .25 mile

|

Control symptoms; progressive return to ADLs

|

|

Subacute

|

Basic Training/ Controlled Motion - progress to Intermediate-Adv Return to fxn |

4-12 weeks

|

intermittent; activity-based symptoms

|

Decreased ability to move under a load (lift/carry) under variable conditions; some level of disability

|

Progressive return to IADLs and limited physical work

|

|

Chronic |

Intermediate-Adv Return to fxn

|

3-6 months |

progressive conditioning for executing repetitive movements/ loads correctly |

Return to maximal functional level; injury prevention

|

Return to work, recreation, sport |

|

Chronic syndrome "Persistent" |

Pain management strategies; home program |

6+ months |

Persistent pain symptoms are somewhat unresponsive to interventions |

Functional limitations persist; may limit engagement in life activities (home, work)

|

Control flare-ups, pace and prioritize activities; gain and maintain endurance |

Treatment-based classification strategies can help prioritize interventions based on the PT examination findings. Symptoms of spinal pathology can overlap, therefore, the physical therapist will develop a plan of care based on special tests and measures which lead to a movement-based syndrome classification.

In your clinical practice, you will encounter references to several classification systems (e.g., McKenzie, Sahrmann approach, Delitto, Williams flexion). If you can focus your exercise application on a solid rationale of kinesiology, keen observation, patient input, and understanding of pathology, then you can successfully collaborate with your PT partner on treatment planning and modification to reach maximum function.

Centralization refers to movements that minimize radicular findings, namely, that isolate symptoms in the spine and remove or reduce symptoms that are lateral to the spine or extend into the extremities. Activities that centralize symptoms generally lead to decreased mechanical strain to the affected spinal unit. Peripheralization is a lateral spreading of symptoms from the spine toward or into the extremity. Activities or positions that result in radiating symptoms away from the spine are avoided.

Click here to see an image of centralization vs. peripheralization

|

Spinal Impairment Classification |

Position(s) of ease ("Bias" position) |

Exacerbating positions |

Principles of acute management |

|

Traction Syndrome |

Non-weight bearing |

Standing, walking, running, coughing. Activities that increase weight bearing in the spine |

Traction Aquatic therapy Gravity-eliminated positions

|

|

Immobilization Syndrome |

Limited limb movements |

Spine is hypermobile; any load that increases stability demand on the spine (reaching, lifting, bending) |

Basic stabilization exercise Soft collar or other temporary orthosis |

|

Mobilization Syndrome |

Adaptive postures and movements due to lack of segmental mobility in lumbar spine or impaired SI mobility |

Movements into the area/restricted motion |

Joint mobilization Spinal and hip ROM; fascial mobilization Basic stabilization exercises |

|

Extension Syndrome |

Slightly flexed with lateral shift; Extension testing decreases or centralizes symptoms |

Flexion, limb loading |

Correction of lateral shift Basic prone extension exercises Hip and trunk stretching |

|

Flexion Syndrome |

Flexed posture, posterior pelvic tilt |

Extension, standing |

Hip and lumbar flexion exercises Spinal stabilization |

|

Postural Syndrome |

Symptoms are due to prolonged, sustained postures that change length-tension relationships and result in pain; pain generally does not change with motion testing |

Postural education and awareness; flexibility and strengthening postural muscles; increasing postural endurance |

|

Dysfunction Syndrome |

Intermittent pain, typically occurring in end-ranges of motion; soft tissue shortening/adaptation is involved; Classification is further specified by likely involved structures (e.g., gross movers, nerve root) |

Progressive stretching and self-ROM exercises to increase restricted range; instruction in activities to prevent recurrence |

|

Derangement Syndrome |

Symptoms increase when there is motion in a cardinal plane or in combined planes of motion |

Joint mobilization Correction of adaptive shifts Flexibility of spine, hip, and trunk Progressive stabilization with limb loading |

Before selecting the most appropriate intervention for your patient, it is important to have a firm understanding of involved structures and tissues, healing stages, and risk for recurrence or further injury.

PTAs provide an extensive amount of education to patient's during all stages of healing. By integrating kinesiology and pathological knowledge, the patients you work with will be more likely to understand the why of the exercise. Patients want to get better, and PTAs can help patients build the necessary confidence to believe in the evidence: progressing posture, movements, and performing the selected exercises consistently and as prescribed, is time well spent.

When thinking about your role, plan for data collection, options for modifications, and indications to communicate with the PT. By planning ahead, you can have multiple interventions to choose from based on the patient presentation and response. Most importantly, you can be listening, feeling, and watching for signs and symptoms which indicate the patient is unable to safely participate in physical therapy.

First, do YOU have any questions about the patient's condition and readiness for treatment? Do you have any questions or concerns about your own confidence and skill set to move forward with treatment? Are you uncertain about elements in the plan of care (including precautions and contraindications) or the PTs directions? If you have questions in these areas, consult the supervising PT for clarification and direction.

Decision-Making Strategies

1. Start with subjective data collection

Clinical pearl: let them know you believe movement is valuable and important by asking about it first

Ask the patient about their movement, daily activity, how long they are able to stand/sit/walk, or other relevant functional targets in the physical therapy plan of care.

Then, ask your patient about other signs and symptoms that relate to the complaint, this may include pain, sensory changes, and aggravating positions or movements.

Ask your patient if there are any other general health concerns

2. Make comparisons

Apply your understanding of healing/recovery stages to the subjective data by collecting relevant objective data:

Observe patient movements, positions and postures. Identify position of bias, if any.

Test and measure specific motions, joints, muscles, endurance, or other indicators relevant to the case as needed based on subjective data and observations or as directed by the supervising PT.

Decide if what you hear and what you see matches findings in the physical therapy plan of care and knowledge of healing stages.

Modify and/or progress interventions based on your data and evidence-informed decisions.

Remember, you have the PTA Problem Solving Algorithm process to help guide clinical-decision making.

Video approximately 15 minutes

Fill in the table with interventions you have learned so far that would be consistent with managing acute spinal symptoms. Then use a 0-5 scale to rate your understanding and confidence in selecting the intervention and delivering clear and evidence-based instruction

|

Plan of Care |

Intervention and Parameters |

Self-rating of understanding |

Self-rating of confidence |

|

Educate the patient |

|

|

|

|

Decrease acute symptoms |

|

|

|

|

Teach awareness of neck and pelvic position and movement |

|

|

|

|

Demonstrate safe postures |

|

|

|

|

Initiate neuromuscular activation and control of stabilizing muscles |

|

|

|

|

Teach safe performance of basic ADLs |

|

|

|

After completing the table above, proceed on through the lecture and refresh interventions from Kinesiology. Consider what you already know when intentionally selecting exercises based on impairment classifications.

1. Position yourself in sidelying. Note the amount of side bending in the lumbar spine and weight bearing pressure in the contralateral shoulder and greater trochanter.

2. Repeat with hand towel rolled into a cylinder and placed under waistline

3. Now try this (Look familiar? It comes from PTA 101 Positioning lecture and your Priniciples & Techniques of Patient Care text)

|

side lying |

aligned with trunk and pelvis; supported in midline position; may need bolsters or extra pillows to support trunk in midline |

upper UE supported on pillows and slightly forward |

hip and knee flexion with pillow between knees |

What are the differences in your comfort level? If you needed to be in a sidelying position on a treatment table for greater than 5 minutes, which of the three options would you choose?

Congratulations! This is an example of how you can apply prior knowledge of interventions for soft tissue protection into a therapeutic activity that allows the patient to assume a position of ease in sidelying.

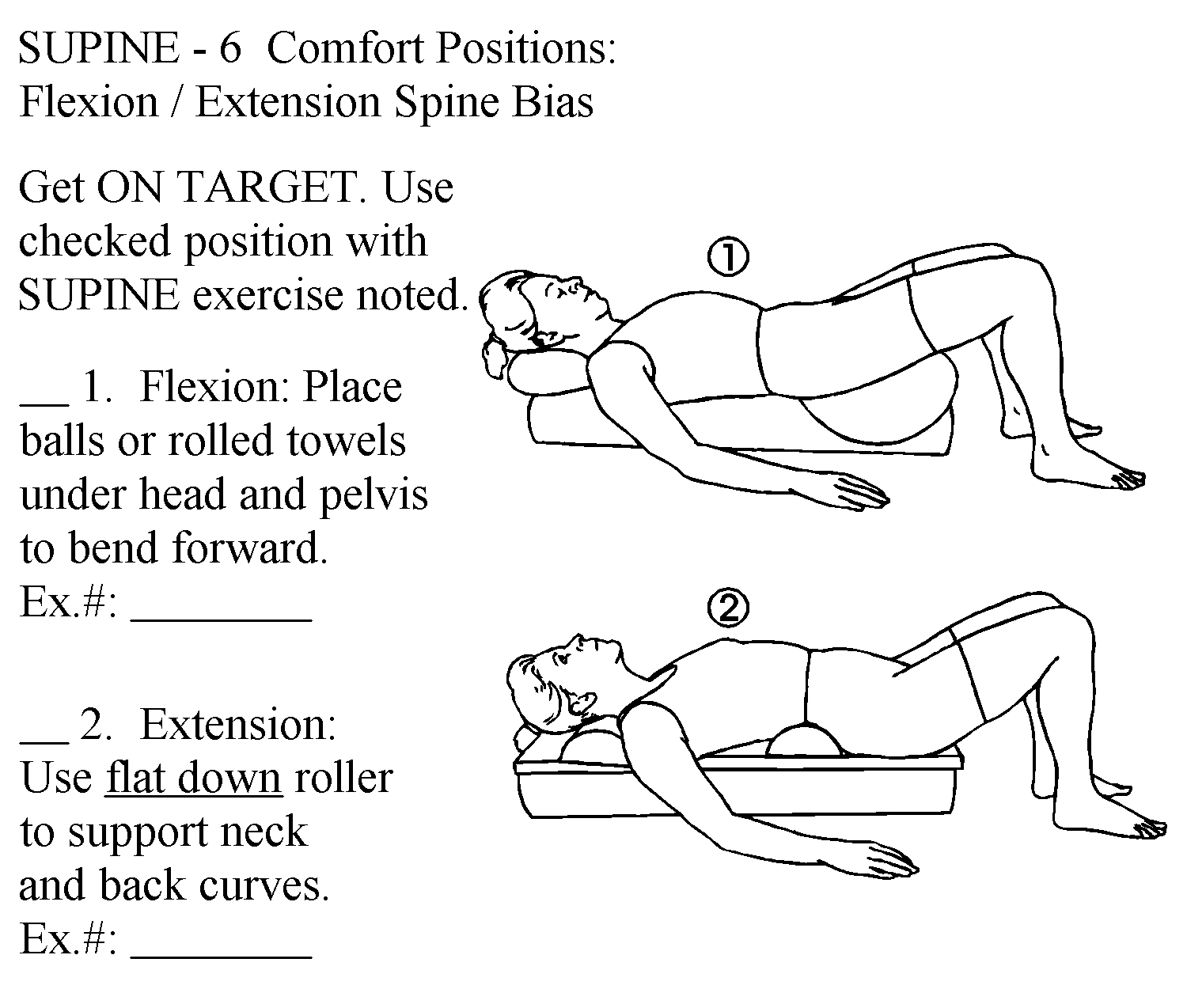

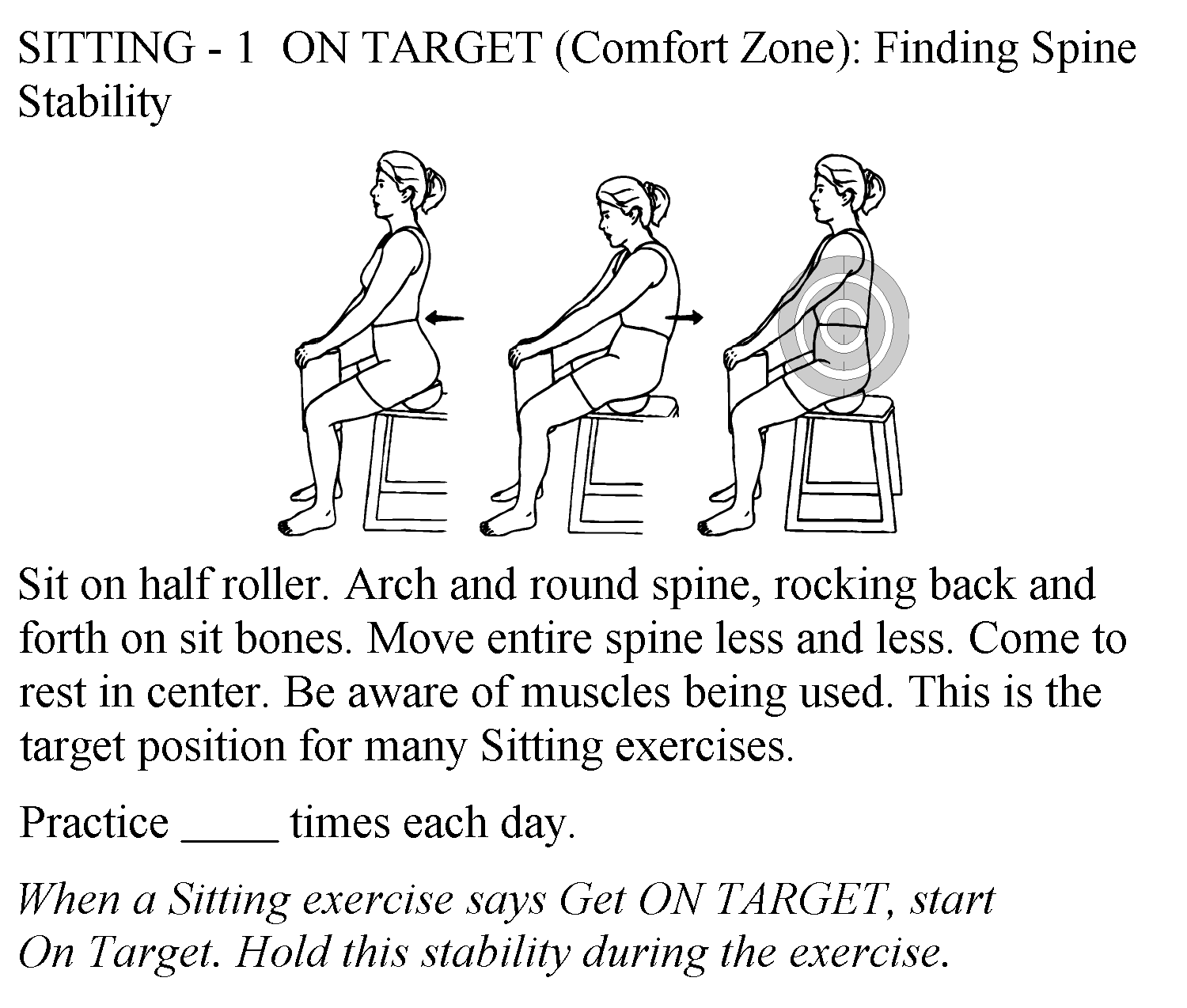

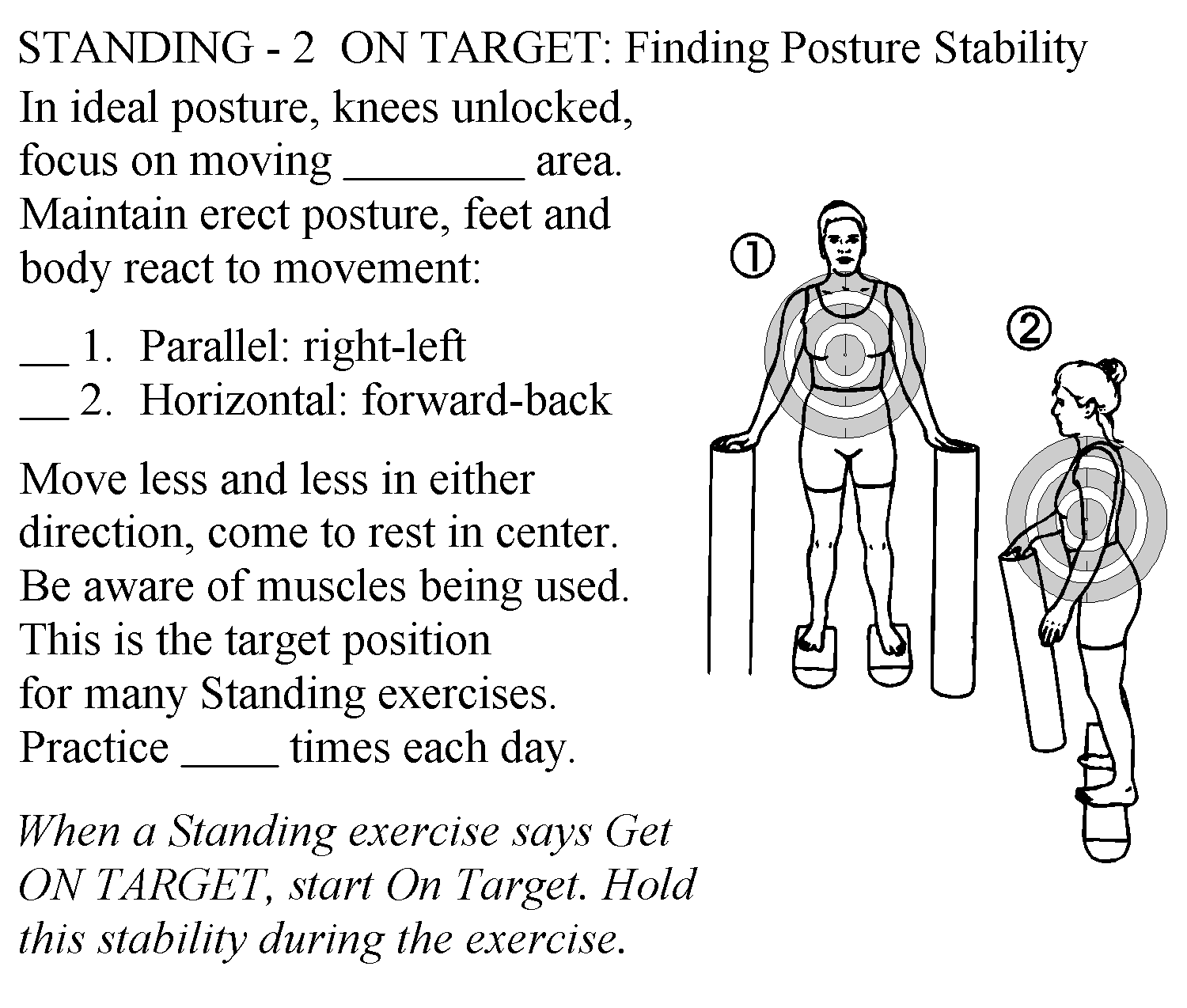

Note: All images in this section are attributed to: Olson S, VHI Exercise Images , Tacoma, Washington:Visual Health Information, 1999

All patients should be engaged in motor learning and training regardless of their functional level. Specific training elements include:

Position of bias = position of symptom relief; also known as the "resting position". This image shows how to teach a patient to use the position of ease for comfort.

Neutral spine = spine segments maintain neutral motion in all planes while in a position or performing a movement.

Emphasis is on bringing the patient's attention to what reduces symptoms and what aggravates symptoms and then educating and instructing them on methods to find and use positions of relief or methods to assume and maintain a neutral spine as a therapeutic activity.

The goal: increase awareness of muscle imbalances, or habits that lead to spine imbalance, and understanding of how these length-tension relationships affect symptoms.

Kinesthetic Training Examples

Recall from PTA 101L when you practiced moving into anterior and posterior pelvic tilt, then found your "neutral". You used kinesthetic awareness and instructions and feedback from faculty to inform your understanding of how to find that "neutral spine". Here are some other examples of kinesthetic training for function:

Priniciples of kinesthetic training are used when teaching a patient how to use passive positioning for symptom reduction and progression to submaximal exercises and mid-range motions. For example:

The goal: perceive no significant compensatory movement at the spine when performing progresive limb loading activities. Demonstrate neuromuscular control by activating primarily stabilizers (spine) and producing appropriate direction and force of primary movers.

Teach client how controlled and correctly sequenced limb motion influences control of spine symptoms during functional activities: rolling, sit to stand, bending, etc.,

Again - recall from your PTA 101L experience: how did you teach a patient to move from supine to sidelying to sit? You applied principles of limb loading to reduce forces needed to sit up, and part of this included awareness of sequenced movements and minimizing forces on the spine.

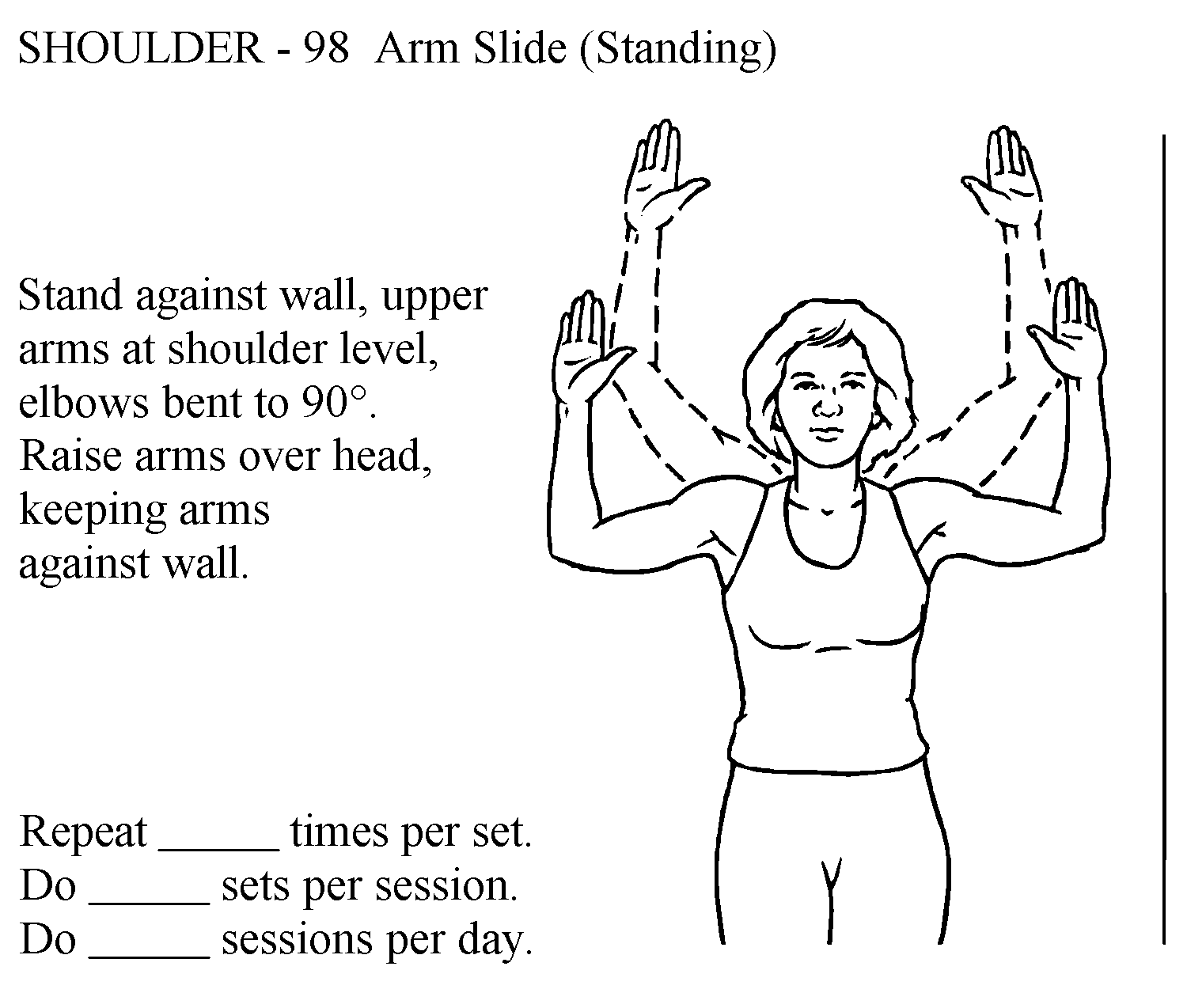

In this image, the patient is trying to control the position of the head and cervical spine while the chest opens and shoulders abduct. Any compensatory motion of the head and neck, like flexing away from the door or being unable to maintain arms against the wall, would be felt by the patient and practiced again to prevent compensation. These observations may also guide decision-making for stretching interventions.

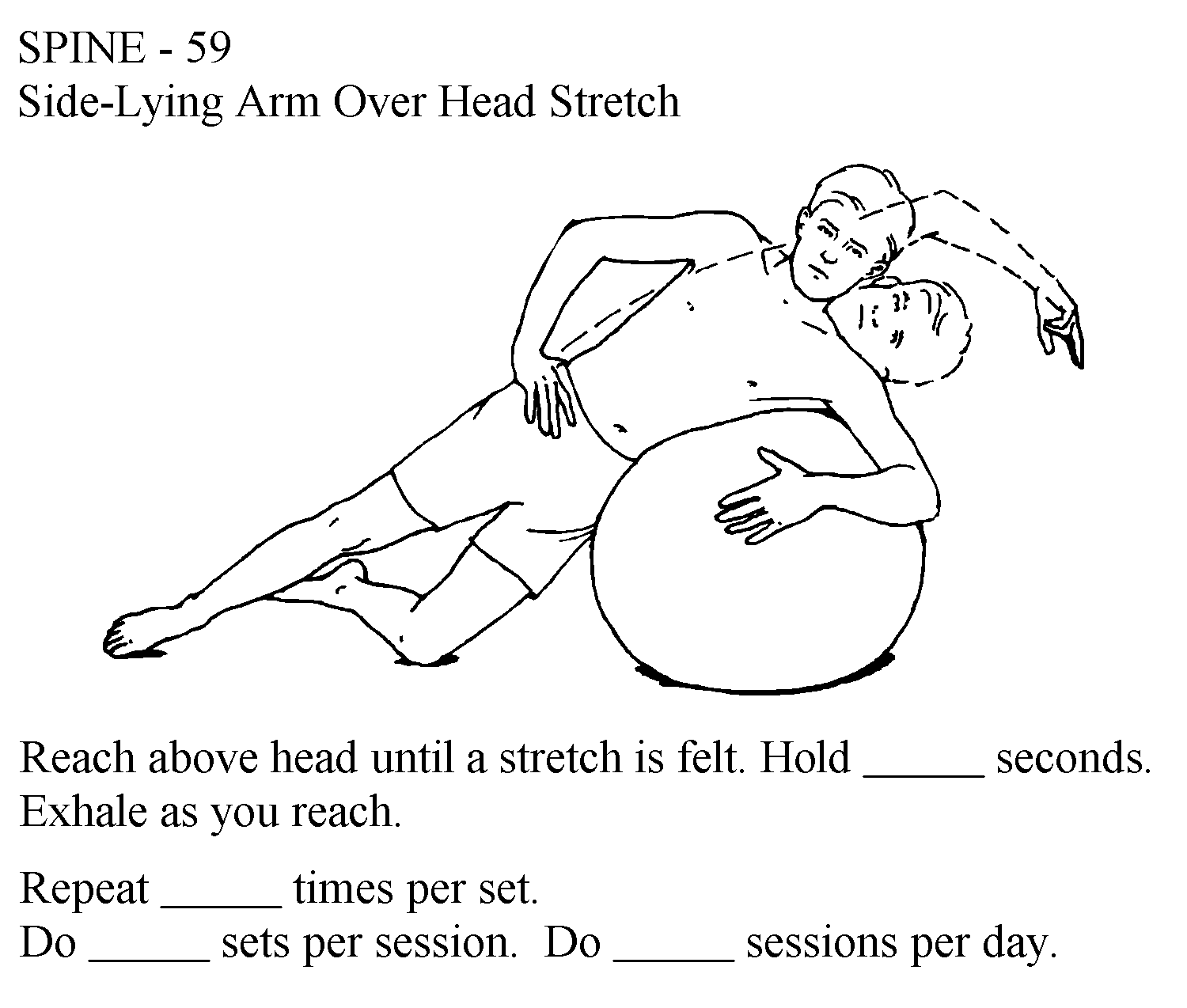

When there are imbalances in postural, passive and active exercises restore length-tension relationships. These exercises and movements are used to mobilize joints and soft tissues. The key element is that these are performed correctly and at low frequency intervals throughout the day. Traction forces are stretching forces which may be used to decompress inflamed nerve root structures, thus decreasing pain.

The goal: Minimize or eliminate restrictions that prevent assuming and maintaining a neutral spine during sustained positions and activities

Self-mobilization examples for areas of hypomobility:

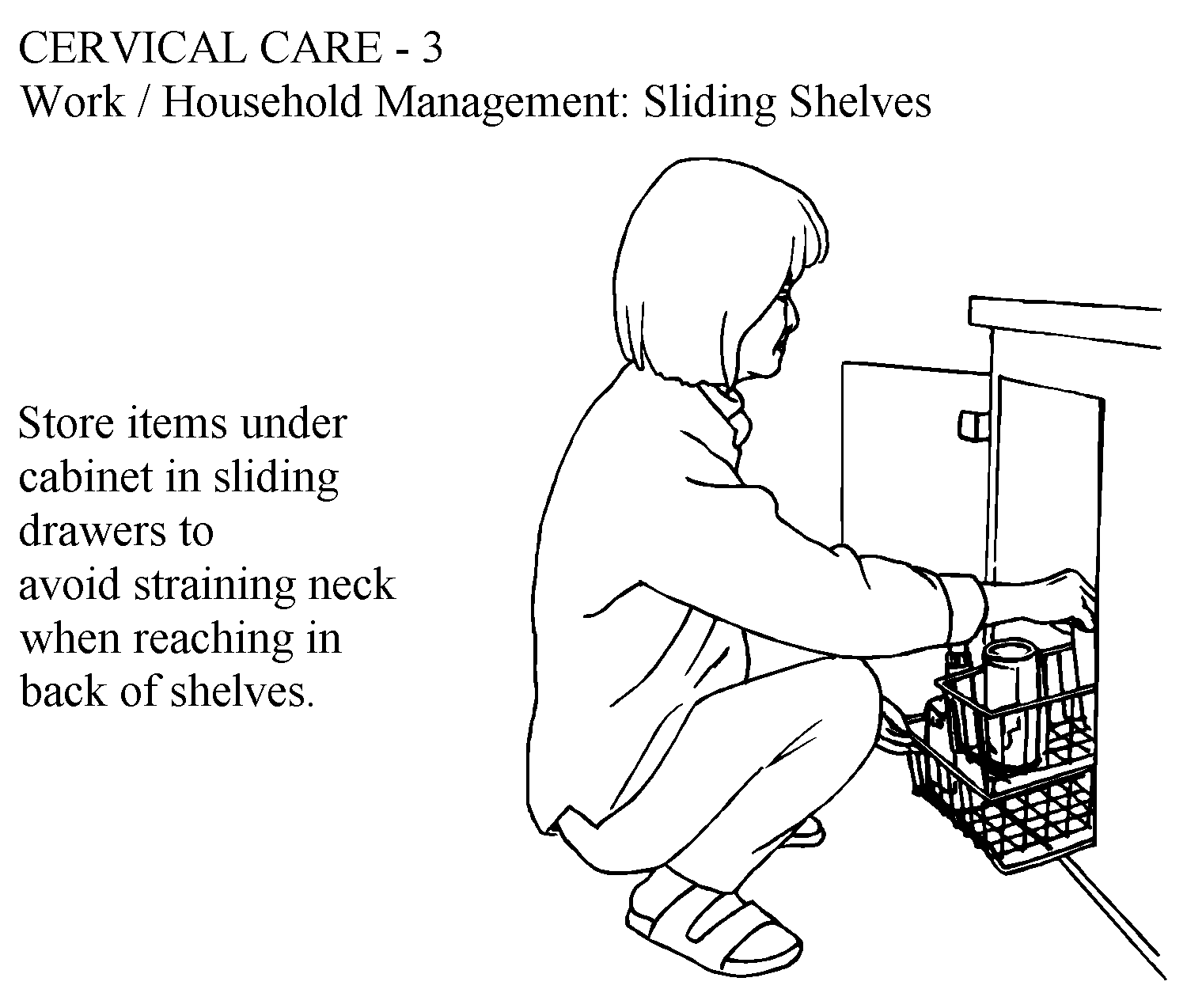

Functional training should be patient-specific as determined by the physical therapy plan of care. Patients should begin to practice basic functional training without the use of a load, then progressively work towards performing activities typical for their home and work environment.

In this example, a patient with a history of cervical pain would practice placing and removing moderately light objects on low surfaces while minimizing stress and strain to the neck using sliding shelves:

The Dutton text provides excellent examples of these progressions for the cervical and lumbar spine

Shirley Sahrmann has adapted a sequence of exercises for spinal stabilization using limb-loading principles.

Video approximately 5 minutes

We suggest that you practice on your own or instruct a willing participant in each of the exercises. Many patients will need continuous feedback in the initial stages of learning and your own experience with practice can help you appreciate concepts of feedback and motor control

Approximately 6 minutes

|

Intervention |

Early Training; Protection |

Basic Training; Controlled Motion |

Intermediate to Advance Training; Return to Function |

|

Training in safe movement and postures (kinesthesia/proprioception) |

Pelvic tilt; cervical retraction PROM-AAROM-AROM |

Active spinal stabilization in progressively more challenging positions (supine, prone, quadruped); stabilization during functional activities |

Integrates spinal stabilization into ADLs/iADLs |

|

Mobility/Flexibility |

Stretching in pain-free ranges (spine and extremities); gentle joint mobilization |

Gentle motion into mildly painful ranges; limb stretching without activation of spine symptoms |

Stretching into limitations, including discomfort |

|

Core Stabilization; muscular strength and power |

Passive positioning with isometric and gentle, progressive limb loading |

Progressive stabilization with limb loading in dynamic postures; begin abdominal and limb strengthening and endurance training |

Progression to dynamic trunk strengthening using challenging surfaces and resistance |

|

Cardiopulmonary Endurance |

Limited; work in position of ease and protect affected joints |

Low to moderate intensity (RPE) with emphasis on joint protection; target activities that can be performed in position of bias |

High intensity -sustained cardio activity consistent with health promotion (30 min, 3+ x week) |

|

Functional Activities |

Safe postures; safe and adaptive techniques for rolling/supine to sit |

Functional activities that include limb motions while maintaining stable spine (reaching, lifting, bending, squatting, kneeling, etc.) |

Practice prevention Individualized instruction in specific, higher level functions the patient engages in at work/home/sport |

Fill in the table with interventions you have learned so far that would be consistent with managing subacute / controlled motion spinal symptoms. Then use a 0-5 scale to rate your understanding and confidence in selecting the intervention and delivering clear and evidence-based instruction

|

Plan of Care |

Intervention and Parameters |

Self-rating of understanding |

Self-rating of confidence |

|

Educate the patient in self-management and how to decrease episodes of pain |

|

|

|

|

Progress awareness and control of spinal alignment |

|

|

|

|

Increase mobility in tight muscles/joints/fascia |

|

|

|

|

Teach techniques to develop neuromuscular control, strength and endurance |

|

|

|

|

Teach techniques of stress relief and relaxation |

|

|

|

|

Teach safe body mechanics and functional adaptations |

|

|

|

Now compare your tables for acute and subacute conditions of the spine. How do they differ? Can you see indications for a progression? Would you be able to identify when it is appropriate to progress a patient? Can you provide patient-centered education in the above areas? Use the CAN YOU HELP ME? forum to discuss your findings.

I encourage you to complete the tables and share ideas in the course forums. Consider creating a brief video and posting some exercises you might select for a patient with a subacute or acute condition.