|

|

|

|

|

|

Before looking at the whole grains article below, here is some background information.

There are three calorie-containing nutrients in food. Those are:

Sugar is a carbohydrate with a more simple chemical structure than starch and is found naturally in many foods. Food sources of natural sugar include fruit, vegetables and milk. Sugar is also commonly added to many foods in the form of white table sugar (sucrose), honey, corn syrup or fructose.

Starch, also known as a complex carbohydrate, is present in foods such as cereals, whole grains, rice, pasta, potatoes, peas, corn and legumes.

Fiber, also a complex carbohydrate, is found in ALL of plant origin that are "whole". Whole wheat flour has fiber in addition to starch while white flour has only starch. A food label that lists "wheat" flour is talking about "white" flour.

Foods containing natural sugars and/or fiber are generally very nutritious, providing many vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals (natural plant chemicals), antioxidants and fiber.

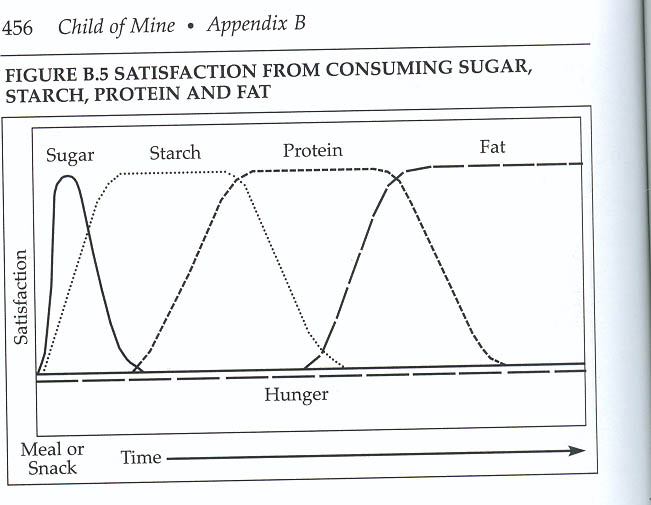

Fiber is not digested so it does NOT pass into the blood then travel to cells and give us energy. Sugar, starch, protein and fat are all digested but at different rates, as described in the next graph. As the graph indicates, sugar is very quicky digested and absorbed and satisfies hunger for only a short time.

The New York Times, March 4, 2003

For Unrefined Healthfulness: Whole Grains

By JANE E. BRODY

Carbohydrates have been taking a beating lately, blamed for the growing obesity epidemic, a raised risk of heart disease and diabetes, among others. To be sure, the carbs that predominate in the American diet -sugars and refined starches-- deserve much of this unsavory reputation.

Consumed to excess as they are now, refined starches act like sugars. Each is widely considered a major culprit in making people overweight, and being excessively overweight adversely affects blood lipids andblood sugar, fostering heart disease and diabetes.

But there is another far more wholesome kind of carbohydrate-rich food whole grains, which make up only 5 percent of Americans' carbohydrate consumption.

Whole grains contain health-enhancing bran (the outer layer) and germ (the internal embryo) naturally found in all grains. When grains are refined to make white flour and white rice, for example, the bran and germ and all their healthful nutrients, antioxidants and other disease-fighting plant chemicals are systematically removed.

In January, researchers summarized the numerous health advantages of substituting whole grains for most of the refined sources of strch now dominating Western-style diets at a conference exploring the health benefits of traditional Mediterranean-style foods. Oldways Preservation & Exchange Trust of Boston and the Harvard School of Public Health sponsored the conference.

The surgeon general's goal is for all Americans to consume at least three servings a day of whole grains, but the nation's daily average is now only about half a serving. Only 13 percent of Americans include at least one serving of whole grains in their daily diets.

The Food and Drug Administration allows food manufacturers to claim health benefits for their products with at least 51 percent whole grains by weight and less than 3 grams of fat per serving. It states, "Diets rich in whole-grain foods and other plant foods low in total fat, saturated fat and cholesterol may help reduce the risk of heart disease and certain cancers."

Whole grains contain no cholesterol, are low in fat and high in dietary fiber and vitamins and are also a good source of minerals. Though whole grains are concentrated packets of starch, they contain about 10 percent to 15 percent protein. But it is the indigestible fiber and phytochemicals in whole grains that render them stars in disease prevention.

A Role in Weight Control

Refined grains are almost pure starch, long chains of molecules of glucose, the blood sugar. Like sugar, most foods made from refined grains are rapidly digested and absorbed into the bloodstream, causing an abrupt rise in blood glucose and prompting the pancreas to spew out insulin to move the excess glucose out of the blood and into cells for energy and storage.

The sudden influx of glucose can cause an overproduction of insulin that results in enough of a drop in blood glucose to cause hunger to return in an hour or two, prompting people to eat between meals-- often snacks of sugars and refined starches.

But when a food contains all or mostly whole grains, digestion and absorption are slowed by the fiber in the bran and by the protein and fat in the germ, increasing satiety and delaying the return of hunger. People who eat more whole grains tend to weigh less than those who consume fewer.

For example, in a study of 3,627 men and women followed for seven years, those who ate the most whole grains-- more than nine times a week-- weighed five to eight pounds less, on average, than those who consumed the least (no more than twice a week) of these foodstuffs, Dr. Simin Liu of Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston reported.

Highlighting the Benefits

People who eat whole grains are healthier and live longer. In a continuing study of nearly 34,000 Iowa women, initially aged 55 to 69, Dr. David Jacobs at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health and colleagues found that those who ate at least one serving of whole-grain foods a day, primarily as bread and breakfast cereal, had a significantly lower rate of death from all causes when compared with women who ate almost no whole grains.

Several large prospective studies have highlighted the contributions whole grains can make to health and longevity.

For example, among the Iowa women, whole grain intake is directly related to a decreased risk of coronary heart disease, the leading killer of women and men in the United States.

Likewise, a Finnish study of 21,930 male smokers and an American study of 43,757 male health professionals found a reduced risk of heart attacks among those who ate the most whole-grain bread and cereal.

Although soluble fiber in whole grains is known to lower artery-damaging cholesterol, other components of whole grains contribute to cardiovascular protection, including antioxidants, phytic acid, lectins, phenoliccompounds, amylase inhibitors and saponins. Dr. Joanne L. Slavin, a professor of food and nutrition at the University of Minnesota, says the protection probably comes from a combination of compounds in whole grains.

Dozens of studies have shown that cancer risks are reduced by eating whole grains. As Dr. Slavin noted in The Journal of the American Dietetic Association: "Whole grains are rich sources of a wide range of phytochemicals with anticarcinogenic properties. Some of these phytochemicals block DNA damage and suppress cancer cell growth."

The fiber in whole grains increases fecal bulk and speeds the transit of stool, decreasing the opportunity for mutagens to damage cells and cause cancer of the digestive tract. In addition, Dr. Slavin noted, hormonally active lignans in whole grains "may protect against hormonally mediated diseases, such as cancers of the breast and prostate."

Whole grains can also help to counter the current epidemic of Type 2 diabetes. Whole grains have a low glycemic index: their consumption results in only small rises in blood sugar and insulin release.

In large studies of men and women, higher intakes of cereal fiber (from the whole grains) have been linked to a reduced risk of diabetes.

In the Nurses' Health Study of nearly 90,000 women and the Health Professionals' Study of nearly 44,000 men, those who consumed the most cereal fiber had about a 30 percent lower risk of developing Type 2diabetes, independent of body weight.

More Whole Grains

Dr. Slavin noted that only about 5 percent of the grain foods in the American diet are in the form of whole grains, primarily whole wheat and oats. But whole grain is the main ingredient in about 18 percent of ready-to-eat cereals, suggesting that Americans can easily increase their whole grain intake by eating right at breakfast and steering clear of sugary, highly refined cereals that line supermarket shelves.

Among the cereals that qualify for the whole grain claim are Wheaties, Cheerios, Wheat Chex, Whole Grain Total, Oatmeal Crisp with raisins or apples, Shredded Wheat, Grape Nuts and Grape Nuts Flakes,Raisin Bran, Life, oatmeal (not instant), Malt-O-Meal and Low-Fat Granola by Kellogg's and Quaker.

Some sweetened cereals also qualify, including Frosted Mini Wheats and Oatmeal Squares.

But cereal is just one source of whole grains, food writers and chefs at the Oldways conference noted.

Possibilities include whole grain breads (check the label: whole wheat should be the first ingredient), brown rice, barley, bulgur (cracked wheat), whole wheat pasta, buckwheat groats (eaten unroasted as porridge or roasted as kasha), wild rice, whole-kernel corn and, to the delight of snackers, low-fat popcorn.

In addition, many whole grains less commonly eaten in America are worth discovering. These include grano, farro, millet, spelt, sorghum and amaranth (the golden grain of the Aztecs). Although rarely available locally, exotic grains can be ordered by mail. Sources include Walnut Acres in Penns Creek, Pa.; theVermont Country Store in Weston, Vt.; Shiloh Farms in Sulphur Springs, Ark.; and H. Roth & Son in NewYork.

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company